|

Donatists One of the very basic questions in religion has to do with priests, nuns, witch-doctors, bishops, popes, imams, caliphs, and so on. How can very fallible humans be the messengers of God?

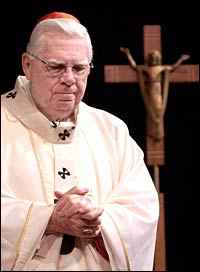

One of the very basic questions in religion has to do with priests, nuns, witch-doctors, bishops, popes, imams, caliphs, and so on. How can very fallible humans be the messengers of God? The question took on a sharp focus when the Boston archdiocese of the Roman Catholic church revealed that it had been covering up instances of child molestation by its priests. The faithful had some questions, mainly: How could the local authority, namely Cardinal Bernard Law, allow priests to continue in parishes when they were known child molestors? The answer to that question, strangely, goes back to the fourth century A.D. The Donatist heresy of the fourth and fifth centuries launched a theological debate that has smoldered its way through millennia and is still making people crazy today. The question is whether priests, ministers and the like should by definition have better morals than everyone else. The Catholic Church's position on this question is that the priest himself is not as important as the grace of God which fuels his work. This position has created a lot of trouble for a lot of people over the years. And it's all because of the Donatists. Early in the fourth century, the early Church went through one of the most severe persecutions it would ever experience... Well, the most severe it would experience from the receiving end. The last of the Caesars, Diocletian, had made life pretty lousy for the early Christians. He killed many and imprisoned more, and he burned their sacred books when he could find them. The threat of death will do things to a person. Many Christians opted to become martyrs and refused to hand over their books for burning, resulting in their imprisonment or death. Others gave up the books and saved their own necks. These bishops and priests became known as traditores, which means "those who handed over."

That didn't sit well with many in the flock, especially those who had gone underground or had spent time in prison for refusing to hand over their books. This group was a minority, due to most of them having been killed, the major hazard of the martyrdom strategy. Donatus of Casae Nigrae was a North African Christian who felt that the traditores were unworthy to administer the Holy Sacraments of the church. Although he didn't found the opposition movement, it was named after him anyway. Donatus lived in Carthage, Tunisia, where the split between traditores and the martyr-loving demographic was especially ugly. The local bishop was Caecilian, a traditor, and he had been consecrated as bishop by another traditor. At the time, bishops were elected by their local congregations, so the majority of Christians in the region didn't care about the traditores issue. The ones who did care, however, were royally pissed. First, Donatus and his friends tried to depose Caecilian by working within the system, gathering a council that voted to strip Caecilian of his position. With the firm support of the people and the advantage of incumbency, Caecilian pretty much told the Donatists to go fuck themselves and insinuated that the martyrs were just idiots with a death wish, who perhaps would rather be glorious martyrs than, say, pay their debts, which he suggested were considerable. Much like spanking a masochist, persecuting a pro-martyrdom sect is somewhat problematic. It just encourages them. (A splinter from the Donatists known as the Circumcellions took this to lemming-like extremes.) The Donatists named an alternate bishop, and to bolster their position, they declared that any sacrament administered by a traditor was invalid. The goal of this argument was simply to invalidate Caecilian's consecration as bishop, but it set off a panic in the Church, which had by now consolidated power around the Rome diocese. If you could retroactively invalidate a sacrament due to the sins of the person performing it, then anarchy ruled. For instance, no one could be certain their baptism was valid, because a priest might be exposed at some later date as a secret traditor, thus invalidating all the baptisms he had performed in the past and consigning hundreds or even thousands of souls unfairly to Hell.

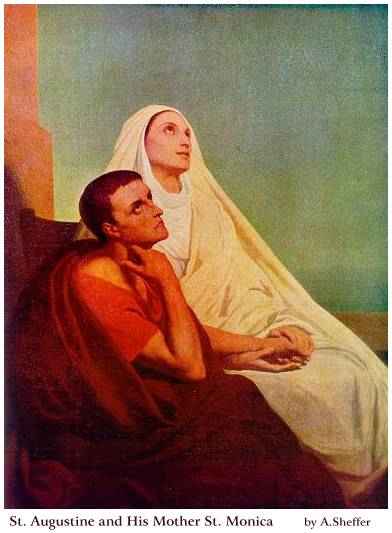

Augustine mounted an argument against the Donatist practice of rebaptizing those who had been baptized first by traditores, and pushed the party line regarding the papal succession from St. Peter—which was still a young and vulnerable concept at the time. Augustine further claimed that some prominent founding Donatists were themselves traditores, which was a very damaging and difficult-to-disprove allegation (given that Augustine was two generations removed from the origin of the sect). In response to the central premise of Donatism, Augustine laid the groundwork for a policy that would shape the church for... well, forever and ever, world without end, amen. The doctrine is formally known as ex opere operato, "from the work itself." Backed into a corner by the Donatist heresy, the Church adopted a sweeping article of faith—the sacraments automatically confer the grace of God by their own inherent quality, and not ex opere operantis, from the merits of the person who performs the work. What that means, in the broadest possible terms, is that a sacrament remains holy even when the person administering the sacrament is not. Ex opere operato was effectively the rule of law after the fifth century, but it wasn't officially written into canon until the Council of Trent in 1547 when it became an issue in the Protestant reformation. The argument would become a central point in the church's battles with later heretics, such as the Cathars, whose piety and modesty made the corrupt Roman clergy of the day look bad by comparison. In that particular conflict, Rome made it quite clear that the priestly conduct was simply of no concern to the Church, and that this lack of concern was explicitly because of the ex opere concept (sometimes articulated as opus operans). Pope Innocent III sent the Inquisition to crush the Cathars on the basis of this principle, first carved out in Carthage: Nothing more is accomplished by a good priest and nothing less by a wicked priest, because is it accomplished by the word of the creator and not the merit of the priest. Thus the wickedness of the priest does not nullify the effect of the sacrament, just as the sickness of a doctor does not destroy the power of his medicine. Although the "doing of the thing (opus operans)" may be unclear, nevertheless, the "thing which is done (opus operatum)" is always clean.Ex opere operato was reiterated as recently as the year 2000, when the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (the modern name for the Inquisition) issued a clarification:

Celebrated worthily in faith, the sacraments confer the grace that they signify. They are efficacious because in them Christ himself is at work: it is he who baptizes, he who acts in his sacraments in order to communicate the grace that each sacrament signifies. The Father always hears the prayer of his Son's Church which, in the epiclesis of each sacrament, expresses her faith in the power of the Spirit. As fire transforms into itself everything it touches, so the Holy Spirit transforms into the divine life whatever is subjected to his power.  Although ex opere operato remains sacred, the church has very recently started to make an important distinction. Just because ex opere protects the validity of sacraments performed by pedophile priests, that doesn't mean it protects the priests themselves.

Although ex opere operato remains sacred, the church has very recently started to make an important distinction. Just because ex opere protects the validity of sacraments performed by pedophile priests, that doesn't mean it protects the priests themselves. In Boston, the archdiocese spent decades shuffling priests from assignment to assignment, despite sometimes extensive histories of child molestation. Priests were rarely removed from parish work for pedophilia, even chronic pedophilia, and they certainly weren't defrocked. Even after the scandal reached a point of extreme crisis, the Vatican refused to automatically defrock priests who were found guilty of molesting children. That's changed only recently. In 1996, Cardinal Law quietly agreed to let Rev. Robert Meffan retire, after he had been accused of molesting teenage girls who were studying to become nuns. In a 1996 letter, Law wrote: We are truly grateful for your priestly care and ministry to all whom you have served during those years. Without doubt over these years of generous care, the lives and hearts of many people have been touched by your sharing of the Lord's spirit. We are truly grateful.It took more than eight more years for the Vatican to agree to defrock Meffan, and it only did so after the aforementioned letter became public. For a sect that's been dead centuries now, the Donatists have a long reach. |

After Diocletian died, the Christians found themselves dealing with a friendlier empire under Constantine, whose mother was Christian. Now that the threat of death had passed, many of the traditores decided it was a good time to get back into the Christian businesses.

After Diocletian died, the Christians found themselves dealing with a friendlier empire under Constantine, whose mother was Christian. Now that the threat of death had passed, many of the traditores decided it was a good time to get back into the Christian businesses.  After duking it out with the Donatist heresy for the better part of 100 years, top Catholic theologian-hit man St. Augustine was brought in to take out the heretics. Augustine was renowned for his debating skills, particularly for making people who didn't agree with him look like idiots.

After duking it out with the Donatist heresy for the better part of 100 years, top Catholic theologian-hit man St. Augustine was brought in to take out the heretics. Augustine was renowned for his debating skills, particularly for making people who didn't agree with him look like idiots.