|

Port Chicago Disaster

The Port Chicago Naval Magazine was built in 1941 and 1942, shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack at the beginning of World War II. Located just outside of Pittsburg, CA, Port Chicago was an ammo dump, where ships were equipped with the greatest firepower the Navy could buy. Handling the heavy ammunition was back-breaking and dangerous work. In the dark days before the dawn of the Civil Rights movement, the Navy had a policy about who should perform such dangerous, back-breaking work. That policy was based on the color of a soldier's skin.

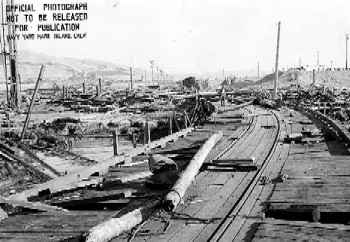

The ammunition dump at Port Chicago consisted of a series of railroad boxcars stacked close together, crammed with everything from bullets to two-ton munitions with the power to level buildings. The ammo was loaded onto the ships using nets and a manual crane. The ammo itself was secured using scrap wood as a packing material. The men were not trained in handling explosives. Port Chicago was a disaster waiting to happen, and it didn't have to wait long. On 17 July 1944, something terrible happened. Exactly what is still unclear. This much we know: At about 10:20 p.m., a massive explosion occurred. There are several accounts of exactly how it went. Either there was one huge explosion, or there were two big ones, one after the other. Everyone agrees the light was blinding. Every one agrees the ground shook for miles around. The blast caused damage for miles around, even as far away as San Francisco.

There were ships in the dock when the event took place. The explosion, or explosions, blew the SS Quinault Victory into bite-sized chunks. The SS E.A. Bryan—millions of pounds of steel—was completely vaporized. The pier was vaporized. And 320 men were vaporized, too. More than 200 of those killed were black, constituting nearly 15% of all African-American casualties in WWII. Another 400 men, mostly black, were injured. But what had happened? The obvious theory is that the ammo on the ships and on the pier ignited and created a monumental explosion, and the official record reflected that for many years. Only recently have other questions come up. The government admitted in 1981 that it had been conducting research into atomic weapons at Port Chicago. It turned out that the explosion just happened to take the hauntingly familiar form of a fireball and mushroom cloud. Officially, the first atomic bomb was detonated a year later in New Mexico. The theory that Port Chicago was a top secret atomic detonation is still just that—a theory—although a lot of people believe a lot of things that are a lot less feasible. The idea has its primary champion in researcher Peter Vogel, whose self-published book on the topic is meticulous and reasonably compelling—except for the book's inception, which was prompted by the author's credulity-testing discovery of a top-secret atomic weapons document at a church rummage sale.

An inquiry determined that "the evidence does not show that there was any intent, fault, negligence, or inefficiency of any person or person in the naval services or connected therewith, or any other person, which caused the explosions". The inquiry discovered that the white officers in charge of the base had been gambling over who could load the most ammunition in the least amount of time, with the result that the loading process proceeded at high speed and frequently resulted in large amounts of ammunition in a small amount of space. The inquiry further determined that this conduct fell under the category of "boys will be boys". As for the African-American enlisted men, well, the Navy was less charmed. According to the inquiry, the white officers had made the best of the situation given "the poor quality of the personnel with which they had to work". Despite the white officers' best efforts to instruct the black enlisted, the Navy determined that the servicemen had a "considerable history of rough and careless handling" of explosive materials.

Needless to say, this wasn't a particularly appealing notion, especially since the Navy wasn't ponying up any improved equipment or training in order to prevent another disaster. Apparently it was less expensive to replace black soldiers than to buy new equipment. More than 250 black enlisted men refused to resume loading munitions, and were promptly imprisoned. Navy Admiral Carleton Wright (rhymes with "white") visited the soldiers and explained to them that they could face potential death loading munitions or certain death in front of a firing squad on charges of mutiny during wartime. Even with this threat hanging over them, 50 soldiers still refused to return to work. Despite the clear questions about unsafe working conditions and the unequal treatment of black enlistees compared to their white commanding officers, the case went to court-martial, and it took the seven white officers less than an hour and a half to sentence the 50 men to dishonorable discharges and prison sentences of eight to fifteen years. Apparently their hearts were moved to spare them a visit to the firing squad. Future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall sued the Navy on behalf of the soldiers. Although he was unable to get the convictions overturned, Marshall succeeded in winning clemency for the 50 soldiers, but not until after the war. After all, the U.S. couldn't take the chance that the Japanese might win the war when the black enlistees refused to pointlessly blow themselves up at a crucial moment.

The Navy ended segregation a couple of years later, in part due to the Port Chicago case, but no one ever took the step to make things better for the "mutineers" until it was far too late. By the late 1990s, only three of the 50 were still alive. One of them, Freddie Meeks, petitioned for a presidential pardon after a Congressional effort to have the convictions overturned was shot down by the Defense Department. In 1999, President Bill Clinton issued a pardon for Meeks. "I appreciate it very much," said Meeks, rather more graciously than many of us might have under the circumstances. Today, the site of the Port Chicago Naval Magazine is a national memorial, dedicated to the lives lost in the explosion and crediting the aftermath of the disaster as the first step toward "racial justice and equality" in the United States. A rather small step, considering 49 felony convictions still stand against the mutineers, but a step nevertheless.

|

All the enlisted men at Port Chicago were black. Their commanding officers were white. That was the insult. The injury would prove to be even more egregious.

All the enlisted men at Port Chicago were black. Their commanding officers were white. That was the insult. The injury would prove to be even more egregious.  And everyone agrees that, when the smoke cleared, a massive crater marked the spot.

And everyone agrees that, when the smoke cleared, a massive crater marked the spot.  The final Naval inquiry claimed it was impossible to determine the cause of the explosion, due to the biblical proportions of the damage. Whether or not the explosion was actually atomic, the incident at Port Chicago still had plenty of scandal and

The final Naval inquiry claimed it was impossible to determine the cause of the explosion, due to the biblical proportions of the damage. Whether or not the explosion was actually atomic, the incident at Port Chicago still had plenty of scandal and  Despite the Navy's utter lack of culpability in the explosion, the brass realized how traumatic the explosion and mass death had been for those who lived through it. Therefore, the Navy granted the white officers at the base leave time, so that they could come to terms with what had happened. However, the black enlisted men—including those injured in the explosion—were simply told to get back to work loading munitions at a new, unvaporized location.

Despite the Navy's utter lack of culpability in the explosion, the brass realized how traumatic the explosion and mass death had been for those who lived through it. Therefore, the Navy granted the white officers at the base leave time, so that they could come to terms with what had happened. However, the black enlisted men—including those injured in the explosion—were simply told to get back to work loading munitions at a new, unvaporized location.  The soldiers were released from prison but forced to remain in the Navy until they had served probation. When they were released, they returned to civilian life with their felony convictions intact and their military veterans' benefits revoked. A grateful nation sends its thanks.

The soldiers were released from prison but forced to remain in the Navy until they had served probation. When they were released, they returned to civilian life with their felony convictions intact and their military veterans' benefits revoked. A grateful nation sends its thanks.