In order to build a case against the notorious Silk Road underground marketplace, a team of U.S. law enforcement agencies spent well over a year casing the site: buying drugs, exchanging Bitcoins, visiting forums and even posing as a vendor, although they did stop short of selling any illicit goods.

From March 2012 until September 2013, Federal agents closely tracked the site, making over 50 drug purchases, according to Jared DerYeghiayan, an agent with the Department of Homeland Security who was part of a special investigation unit looking into the site.

Questioned before a jury at the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, DerYeghiayan was the first witness in the government’s case against Ross Ulbricht, accused of running the Silk Road online marketplace, which according to the prosecutors facilitated the trade of well over a $1 billion in illegal and unlawful goods and services between 2011 and 2013.

Who is the Dread Pirate Roberts?

In opening statements on Tuesday, Ulbricht’s lawyer, Joshua Dratel, asserted that while Ulbricht started the site, operations were handled by another entity, known online only as “Dread Pirate Roberts.”

In the weeks to come, the prosecution must convince the jury that “Dread Pirate Roberts” and Ulbricht are one in the same. First step: Explain how Silk Road operated, and how federal agents obtained the information they needed to identify Ulbricht.

Using an account obtained from an actual user, with the screen name of “dripsofacid,” the task force purchased illegal drugs from 40 dealers in 10 different countries, DerYeghiayan testified. Silk Road first came to their attention because of the mailings of illicit drugs that were coming into Chicago O’Hare International Airport.

In one order, agents purchased 1,000 tabs of ecstasy from a seller in Germany, for $5,499 worth of Bitcoins—Silk Road only accepted Bitcoins. They also made smaller purchases of LSD blotter, cocaine and heroin, among other substances.

Silk Road, as DerYeghiayan described it, sounded like a well-run e-commerce site. It had multiple measures in place to protect the anonymity of users and vendors, as well as to ensure that vendors got paid and customers got the orders they requested.

How it all worked

Of the 50 drug orders the investigation unit made on the site, “nearly all” were delivered, and almost all illicit substances that arrived were verified by a drug lab to be what they were advertised to be, DerYeghiayan said.

Silk Road made such transactions untraceable through a variety of means, including use of the Tor browser for hiding identifying IP addresses and by employing a payment system based on Bitcoin, according to the prosecution.

DerYeghiayan described the processes Silk Road used to ensure all parties were satisfied with their transactions. Silk Road held the Bitcoins in escrow for each purchase until the buyer had agreed to release the money, usually after delivery. Either the buyer or vendor could request Silk Road to investigate a transaction that hadn’t been satisfactorily completed. Silk Road itself made money by adding a small commission fee on top of the transaction, which law enforcement agencies verified by setting up a vendor account.

Even drug dealers get performance reviews

Both buyers and sellers were rated for reliability. Sellers were given instructions not to keep any buyer’s mailing address, which Silk road also deleted from its own servers once the transaction was completed. Buyers could also choose to encrypt their addresses with a public key provided by the seller, so even Silk Road workers would not have access to the information.

On forums and on a Wiki, the Silk Road site also offered detailed information on how sellers could package their goods to avoid detection by law enforcement, and offered tips to buyers on how to collect such packages in ways that wouldn’t get them caught. One such tip: Don’t answer the bell should the postman ring to deliver the package personally.

All transactions were done through Bitcoins, which offer no methods of identifying their users. Because all Bitcoin transactions themselves are public and tracked through services like Bitcoin.info, Silk Road also offered a “tumbler” service that would further obscure the transactions by splitting them up and passing them through several Bitcoin accounts in random variations before delivering them the vendor.

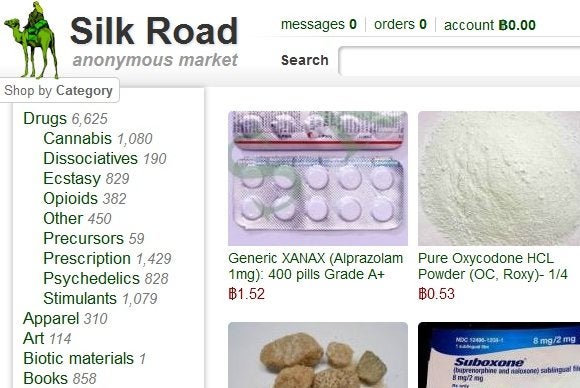

Drugs were the largest group of products that Silk Road sold. By September 2013, just before the site was shuttered by law enforcement, DerYeghiayan’s team had counted over 13,000 different offerings of illicit substances. The site also offered various other items of dubious legality, such as fake identification cards and computer hacking tools. A number of vendors also offered to buy Bitcoins, which users might have had left over from previous purchases.

Texas resident Ulbricht was indicted last February, after being arrested in October 2013 in California. At the time of his arrest, Ulbricht was charged with narcotics conspiracy, engaging in a continuing criminal enterprise, conspiracy to commit computer hacking, and money laundering. Both the charges of narcotics and engaging in a criminal enterprise have maximum penalties of lifetime imprisonment.

Ulbricht has pleaded not guilty to all charges.

U.S. District Judge Katherine Forrest of the Southern District of New York is overseeing the case.