Introduction

Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ) tools, widely used in psychiatry and psychology, exist in several long and short forms. The 10-item AQ (AQ10; Allison et al., Reference Allison, Auyeung and Baron-Cohen2012) is the shortest and recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence as a screening tool for autism in adults (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2012) as it is sensitive to diagnosable autism. It is widely used in research and clinical practice to this end, and therefore it is crucial that the psychometric properties of this measure are robust and continually evaluated when used in new contexts and (clinical) populations. Recently, there has been an increased use of the AQ10 in large-scale studies to measure autistic traits in the general population. Specifically, overall AQ10 scores are being used to quantify the number of autistic traits/tendencies self-reported by an individual, and then correlated with their performance on other tasks (e.g., social psychological skill [Gollwitzer et al., Reference Gollwitzer, Martel, McPartland and Bargh2019]).

Objective

In such research, it is assumed that the AQ10 measures a unitary construct, i.e., trait autism, yet its unifactorial structure was neither tested when the measure was developed, nor following its administration in recent research. There are also concerns regarding its reliability when administered in non-clinical samples (e.g., Jia et al., Reference Jia, Steelman and Jia2019). Therefore, we examined the AQ10’s factor structure and internal reliability, supplementing the original article on its development (Allison et al., Reference Allison, Auyeung and Baron-Cohen2012) and Gollwitzer et al.’s (Reference Gollwitzer, Martel, McPartland and Bargh2019) recent research that used the AQ10 as a measure of trait autism in the general population.

Methods

Using Gollwitzer et al.’s (Reference Gollwitzer, Martel, McPartland and Bargh2019) openly accessible data (Gollwitzer, Reference Gollwitzer2019) – comprising a very large sample of adults (n = 6,595) that had completed the AQ10 in addition to other measures – the following analyses were performed. First, confirmatory factor analysis, with maximum-likelihood estimation, tested whether a 1-factor (i.e., unifactorial) solution was a good fit to the questionnaire data. This was the critical test of whether the AQ10 is a unitary measure of trait autism. Second, parallel analysis, with oblique Promax rotation, explored if there was more than one factor present in the questionnaire data. Finally, we used several approaches to quantify the internal reliability of the AQ10. Together, we conducted this study to examine the psychometric properties of the AQ10 specifically as a measure of trait autism in the general population.

Results

The confirmatory factor analysis indices indicated that a unifactorial model poorly fit the data, with all metrics failing to meet recommended guidelines (see Hooper et al., Reference Hooper, Coughlan and Mullen2008) for ‘good’ model fit (Table 1).

Table 1. Factor Analysis Fit Indices for AQ10.

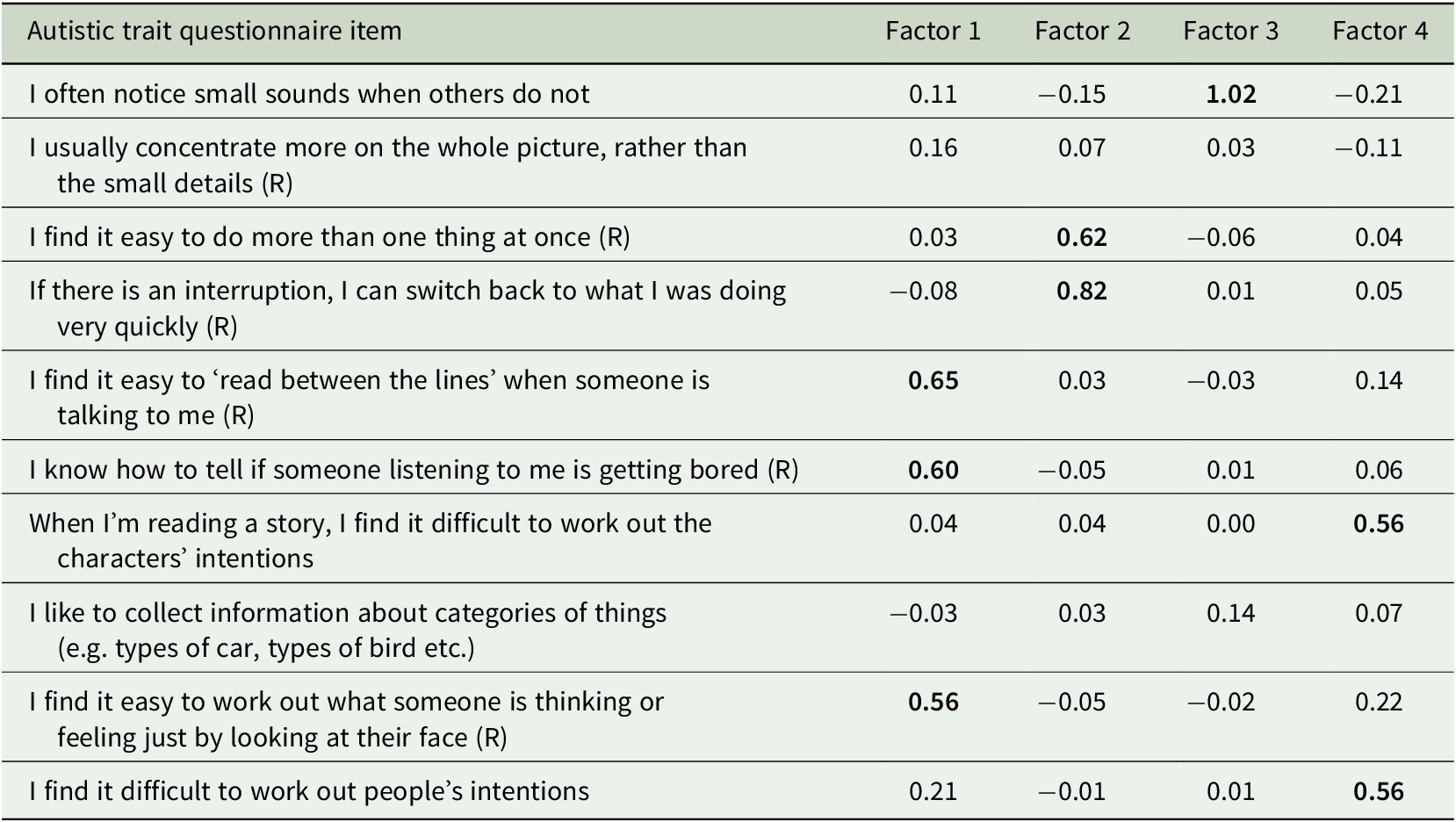

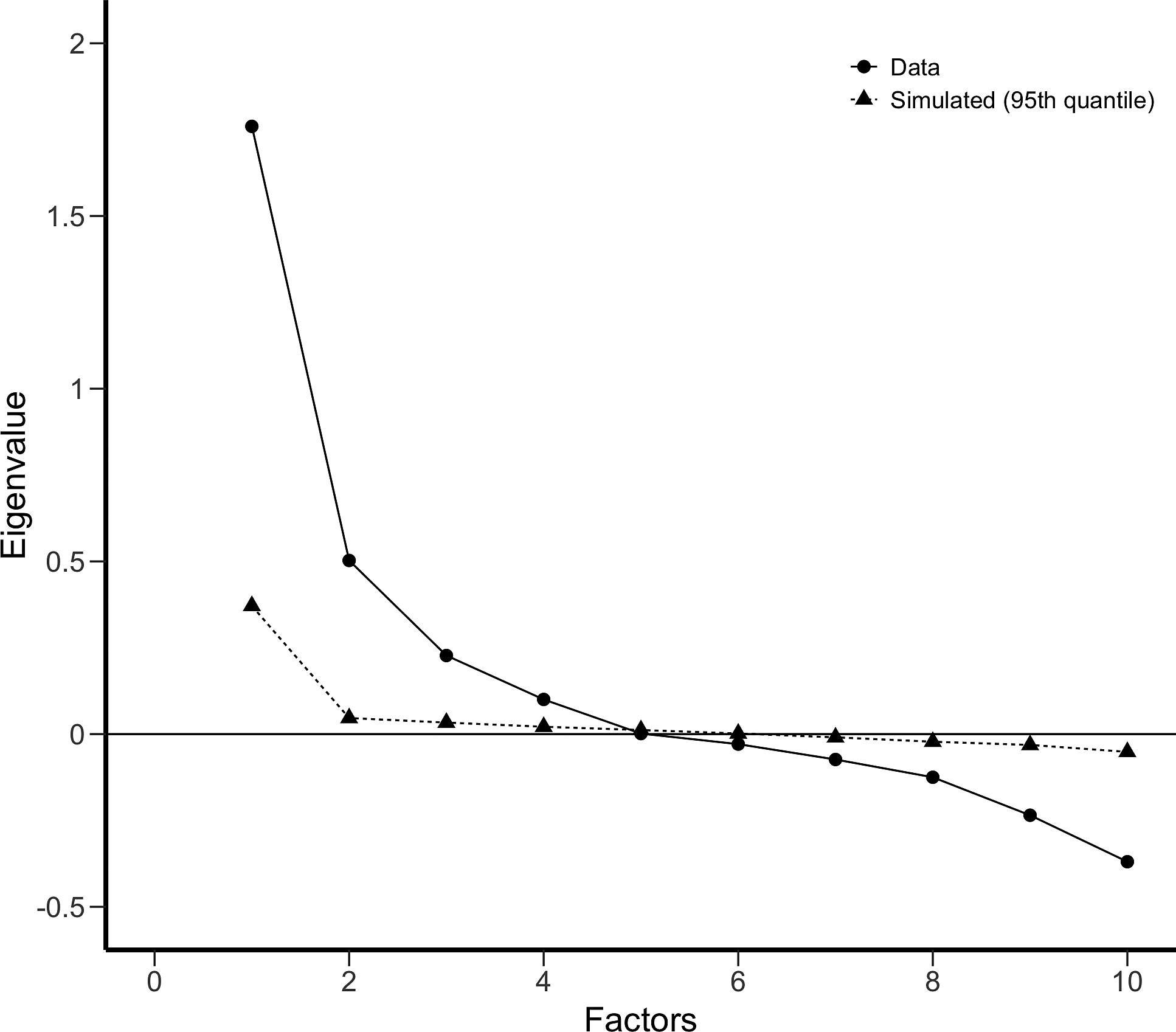

Conversely, parallel analysis showed that a four-factor solution (Table 2 and Figure 1) was more appropriate, with fit indices indicating good model fit (see Table 1).

Table 2. Parallel Analysis Item Loadings of AQ10 Items.

Note. Table shows item loadings of ten items. (R) denotes items that are reverse scored. Item loadings greater than 0.4 are presented in bold.

Figure 1. Scree Plot for Parallel Analysis of AQ10, which suggests that a 4-factor solution was the best fit to the data (Produced using JASP 0.11.1).

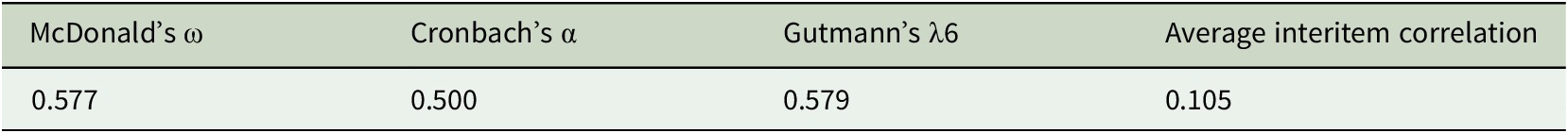

Finally, the AQ10 had poor internal reliability, with all metrics <0.7, which was unsurprising given the weak interitem correlations between the questions (Table 3).

Table 3. AQ10 Reliability Statistics.

Discussions

The results suggest that the AQ10 does not have a unifactorial structure. Rather, it appears to have multiple factors, likely because its items were drawn from 5 different subscales of the full AQ (Baron-Cohen et al., Reference Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, Martin and Clubley2001). Therefore, its factor structure neither reflects autism conceptualised as a unitary construct, nor the dyad of social-communicative and rigid and repetitive impairments that underpin diagnosable autism (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Given that we also found it has poor reliability, this study indicates that the AQ10 may not be a psychometrically robust measure of autism in non-clinical samples from the general population.

Conclusions

The present study is the largest psychometric analysis of the AQ10 to date. However, given the absence of socio-demographic data, it was not possible to conduct further analyses of interest (e.g., measurement invariance in males versus females). Therefore, although the AQ10 is a clinically robust screening tool for diagnosable autism, we caution against its use as a measure of trait autism in the general population until further research is conducted on its psychometric properties. We recommend that, until such research is conducted, AQ10 users should examine and report its psychometric properties, so this questionnaire can be evaluated and refined accordingly.

Author Contributions

ECT and PS conceived the study. ECT, RC, and PS analysed the data. ECT, LAL, and PS wrote the article.

Funding Information

ECT is support by a Whorrod Scholarship, RC by the Economic and Social Research Council, and LAL by the Medical Research Council.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the study are available from https://osf.io/4pd2m/?view_only=db1650b2e86240ddb7a6158a96f6abf5