In praise of failure

In most jobs and most industries, if you do something that doesn't work out, that's a bad thing, and you might get fired. If you write a cover story for a newspaper that turns out to be untrue, you have a problem. If you ship a product that breaks, you have a problem.

If you do something that doesn't work out, that means you screwed up.

Startups and startup investing don't quite work like this.

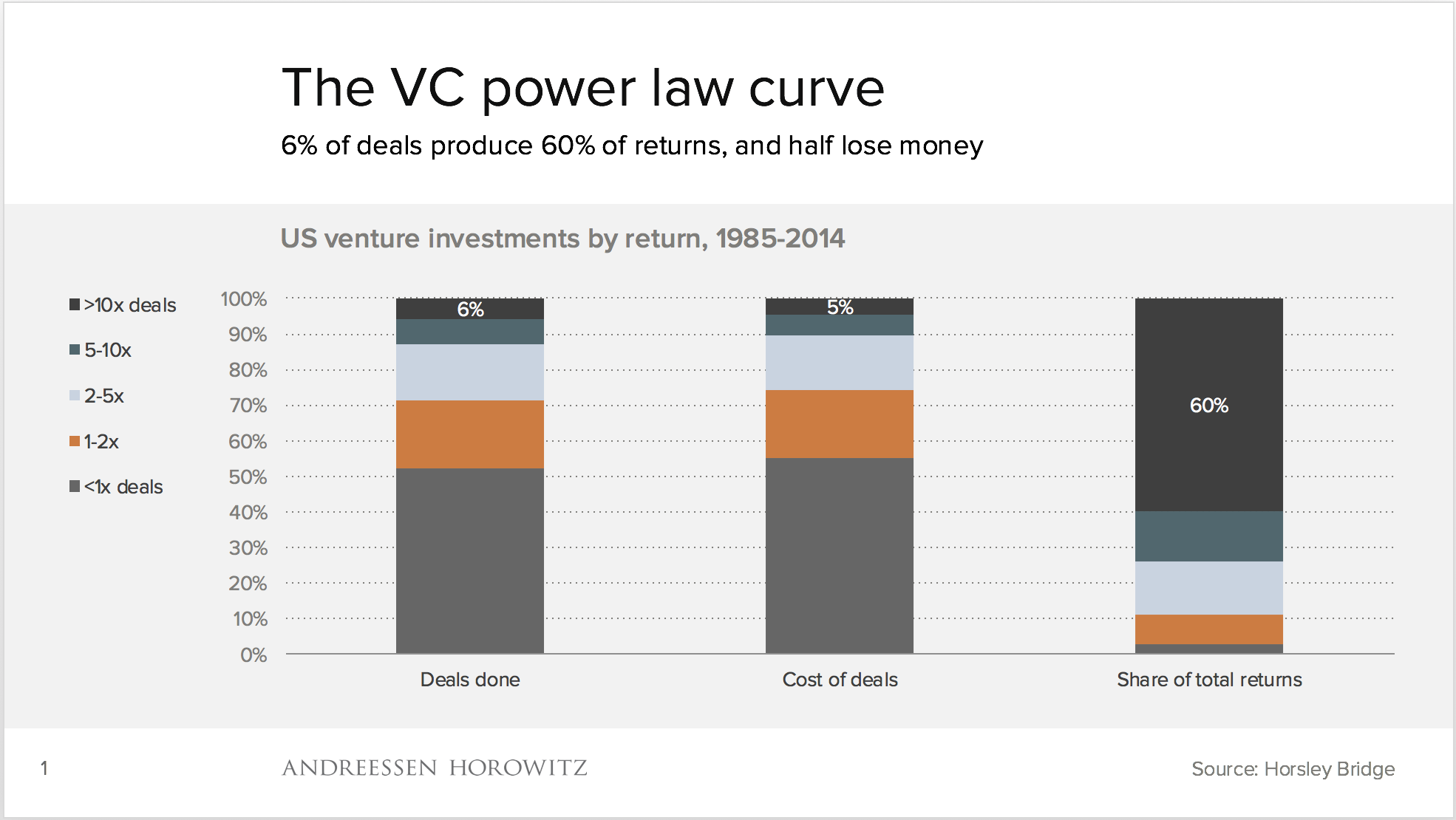

Last year Horsley Bridge (one of our LPs - investors in a16z's funds) shared some aggregate data with us on just over 7,000 investments made by funds in which it invested, from 1985 to 2014. This gives a good way of visualising the world of VC-backed startups. First, the high level:

Around half of all investments returned less than the original investment

6% of deals produced at least a 10x return, and those made up 60% of total returns

Digging into the data to look at the returns of different funds, below:

With the exception of funds that simply flamed out (concentrated in the dotcom bubble), everyone lost money on around half of their deals

But the best-performing funds actually had more <1x deals - more deals that lost money in absolute terms. You could call this the 'Babe Ruth effect' - you take more risks to get the best returns

A fund gets better returns by having more really big hits, not by having fewer failures

That concentration continues when you ask just what a '10x deal' really is - in fact, there’s no such thing. For funds with an overall return of 3-5x, which is what VC funds aim for, the overall return was 4.6x but the return of the deals that did better than 10x was actually 26.7x. For >5x funds, it was 64.3x.

The best VC funds don’t just have more failures and more big wins - they have bigger big wins.

If you're a portfolio manager in a conventional public equities fund and you invest in a bunch of stocks that go down (or underperform the index), you could well lose your job, because your other investments can't make up for that loss. And if a public company went to zero, that would meant that a lot of people had screwed up really badly - public companies aren't ever supposed to go to zero, in the ordinary run of things.

But venture capital funds invest in a different kind of company - they invest in a particular type of startup, one that is much more likely to go to zero, but which has the potential, if it does succeed, to produce something very big. The enormous value created by the startups that really work is possible in a way that's not really true in many other places. It's possible for a few people to take an idea and create a real company worth billions of dollars in less than a decade - to go from an idea and a few notes to Google or Facebook, or for that matter Dollar Shave Club or Nervana. It's possible for entrepreneurs to create something with huge impact.

But equally, anything with that much potential has a high likelihood of failure - if it was obviously a good idea with no risks, everyone would be doing it. Indeed, it's inherent in really transformative ideas that they look like bad ideas - Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon all did, sometimes several times over. In hindsight the things that worked look like good ideas and the ones that failed look stupid, but sadly it's not that obvious at the time. Rather, this is how the process of invention and creation works. We try things - we try to create companies, products and ideas, and sometimes they work, and sometimes they change the world. And so, we see, in our world around half such attempts fail completely, and 5% or so go to the moon.

Clearly, not every new company or new business idea fits this model - not every startup has the potential or the risk we see here, and not every 'startup' is right for VC. Other, these are companies that sit right out at one end of the risk/reward curve, and you have to understand both the scale of the potential risk and the scale of the potential reward.

This is an interesting intellectual challenge for a VC or, more importantly, an entrepreneur: you need to ask not whether this idea will fail, let alone whether it could fail, but rather, ‘what would it be if it worked?’ You need, in a sense, to ‘suspend disbelief’ - to put aside your normal human risk-aversion and skepticism, accept the probability that it could go to zero, and ask if this could 'put a dent in the world', and if so, how big.

Indeed, all of this applies to entrepreneurs even more than it does to VCs. Just as VCs would like only to do the deals that succeed, so would entrepreneurs. But entrepreneurs only get to do one at a time (normally). So an entrepreneur is committing years of their life to just one brilliant, terrible idea, that probably won't work, but if it does, will be enormous. And around half of those commitments fail - there are lots of risks, and lots of ways that these attempts can fail, without it being anyone's fault. If you take a normal, mature company to zero in a few years, you probably screwed up, but if a startup doesn't make it, generally that's just the risk you took. Pulling a company into reality out of thin air, through sheer force of will, isn't easy. But you're only reading this because of the entrepreneurs who took that bet. This is how invention works.

None of this means that failure is good - failure is horrible and painful for everyone. You're not supposed to fail. Nor does it mean that doing stupid things is good, nor that screwing up is good. It certainly doesn't mean that no tech company that failed ever did something stupid or screwed up, nor that no VC has ever made an investment that they shouldn't have. People screw up in tech all the time. But failure is part of risk, and failing, by itself, does not mean that anyone was stupid, or screwed up. Failure just means you tried.