Tryon’s Rat Experiment

Tryon’s Rat Experiment is a multi-decade selective breeding animal experiment begin in the 1930s which rapidly bred enormous differences in a complex psychological trait, maze-running, demonstrating core principles of behavior genetics.

Tryon’s Rat Experiment is a multi-decade selective breeding animal experiment in the 1920s–1940s which employed automated maze-running machinery to minimize measurement error and, using truncation selection, bred two different strains of rats: “maze-bright” and “maze-dull” rats, selected for high & low maze-running performance.

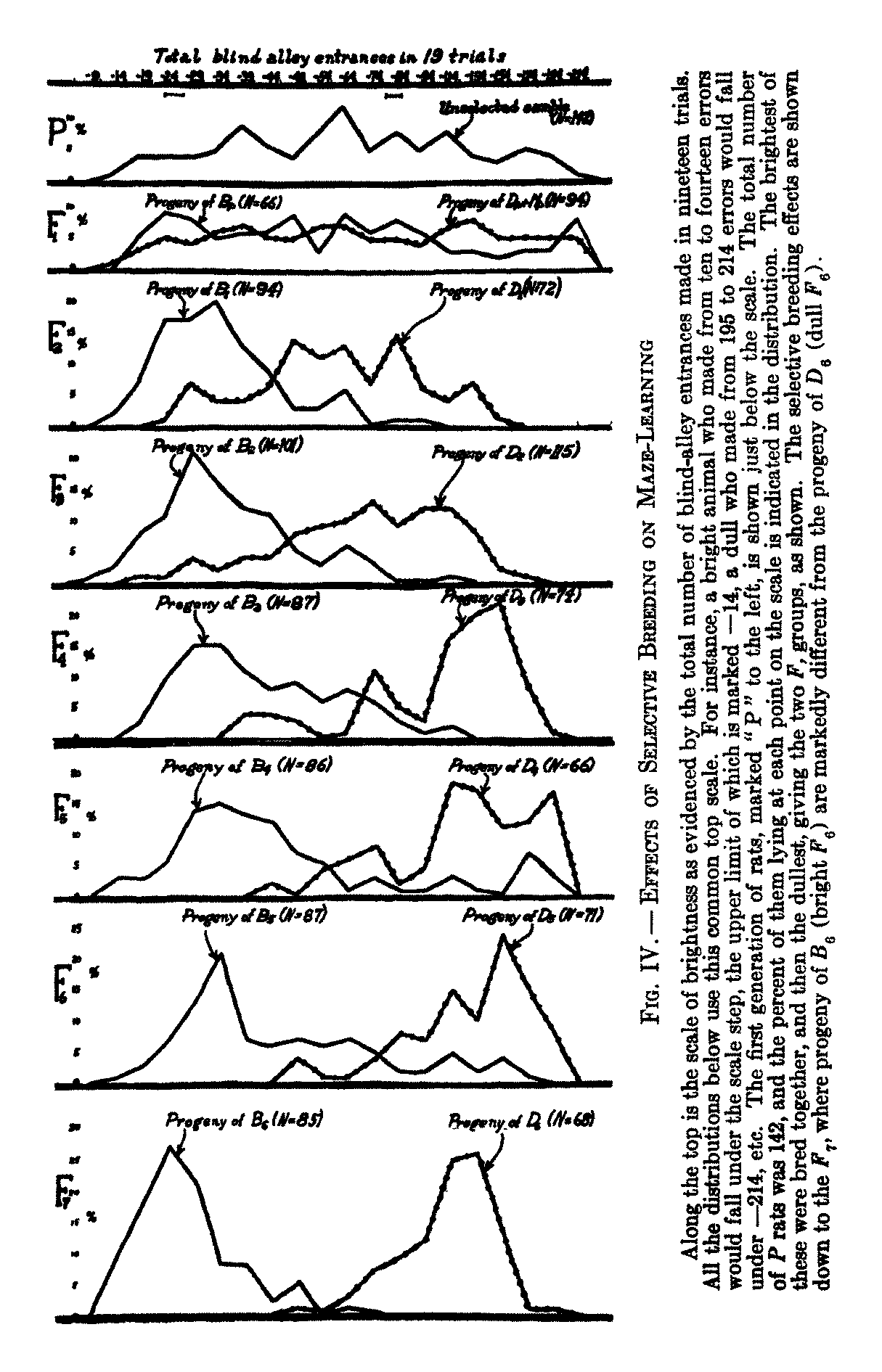

Within a few generations, the rats showed increasing differences in maze-running performance, and the two strains eventually had non-overlapping distributions. Tryon’s Rat Experiment rapidly bred enormous differences in a complex psychological trait, demonstrating core principles of behavior genetics: the heritability of even psychological traits far removed from standard examples of genetics like coat color, and the ability of selection produce large population-wide changes in a short time for even highly polygenic traits like maze-running.

The etiology of the changes in performance were subsequently investigated: the performance changes were not on the g-factor of intelligence, but were more maze-running-specific, and have neurological correlates.

The experiment was widely-cited in psychology and early behavior genetics, and paralleled various later experiments in selection on complex behavioral traits.

Results

Figure 4 from 1940 showing near-complete divergence after 7 generations.

1925, “A Self-Recording Maze”

1927, “The Reliability and Validity of Maze-Measures for Rats”

1933, “An Automatic Recording Device for Use in Animal Psychology”

1935, “The Association Between Brain Size and Maze Ability in the White Rat”

1941, “The Inheritance of Brightness and Dullness in Maze Learning Ability in the Rat”

1951, “The Genetics of Behavior” (in Handbook of Experimental Psychology, 1951)

Rosenthal, R, & Fode, K. (196363ya). “The effect of experimenter bias on the performance of the albino rat”. Behavioral Science, 8, 183-189.

Scott & Fuller 196561ya, Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog

et al 1967, Behavior-Genetic Analysis

1970, “Behavioral Genetics”

1972, “Genetic experiments with animal learning: A critical review”. Behavioral Biology, 197254ya, 7, 143-182

1992, “Tolman and Tryon: Early research on the inheritance of the ability to learn”

Criticism

Rosenthal, R, & Fode, K. (196363ya). “The effect of experimenter bias on the performance of the albino rat”. Behavioral Science, 8, 183-189.

1963 tested the ability of expectancy effects to create ‘maze-bright’-like differences in rats; undergraduate students were told random rats were maze-bright or dull, and there were subsequent small differences which were just barely statistically-significant.

While they do not explicitly cite Tolman or Tryon, they use maze-running as the task and the term ‘maze-bright’, and approvingly quote Pavlov about how supposed genetic effects may in fact be solely environmental. Given how well-known Tryon was, the specific term, and Rosenthal’s broader research paradigm which is purely environmental and his claims to make enormous changes in highly heritable traits by simple expectancy effects like the (debunked) Pygmalion effect, 1963 has been interpreted as implying that Tryon’s rats were not genetically modified and possibly the observed differences were merely Tryon et al’s expectancy effects—maze-brightness becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.1

This is false for many reasons:

p-Hacking: 1963 is highly dubious to begin with: the p-values are all one-tailed (despite Rosenthal’s other experiments supposedly showing that expectancy effects are complex & their directions difficult to predict, making one-tailed unjustified except to make the p-values much smaller2), and despite that, still generally only just p < 0.05 (a classic indicator of a result that will fall prey to the Replication Crisis). Other results of Rosenthal like the Pygmalion effect have signally failed to replicate, and there do not appear to be any replications of 1963.

Too Small Effect: The expectancy effect is far smaller than the genetic effect observed within a few generations, much less the final generation. The genetic effects of selection can easily accumulate; the supposed environmental effect would not.

Irrelevant to Automated Experiments: The mechanism of bias as proposed is impossible—Tolman & Tryon invested great efforts into automated maze-running machinery precisely to make the measurements as accurate & unbiased as possible. Undergraduate students could not have biased the maze-running measurements by handling the rats during testing because there were no humans involved during testing! (Rosenthal does not mention this in either version.)