Iodine and Adult IQ meta-analysis

Iodine improves IQ in fetuses; adults as well? A meta-analysis of relevant studies says no.

Iodization is one of the great success stories of public health intervention: iodizing salt costs pennies per ton, but as demonstrated in randomized & natural experiments, prevents goiters, cretinism, and can boost population IQs by a fraction of a standard deviation in the most iodine-deficient populations.

These experiments are typically done on pregnant women, and results suggest that the benefits of iodization diminish throughout the trimesters of a pregnancy. So does iodization benefit normal healthy adults, potentially even ones in relatively iodine-sufficient Western countries?

Compiling existing post-natal iodization studies which use cognitive tests, I find that—outliers aside—the benefit appears to be nearly zero, and so likely it does not help normal healthy adults, particularly in Western adults.

Iodine deficiency is interesting from the ethical standpoint as one of the most cost-effective—yet obscure—public health measures ever devised which deserves a name like nootropics: a few pennies of iodine added to salt eliminates many cases of mental retardation & goiters.

Background

Supplementation of iodine in salt, water, or oil increases body iodine levels and reduces iodine deficiency disorders ( et al 2002). Supplementing, during pregnancy or infancy, can raise average IQs in the worst-off regions by <13 IQ points1 (close to a full standard deviation); such an increase is of considerable economic value, even in developed countries with iodization programs (see et al 2015 & appendices for a cost-benefit analysis). In an additional bonus for our post-feminist society, females benefit more from iodization than males2. Because salt production is generally so centralized as a bulk commodity extracted from a very few areas, iodization is almost trivial to implement. (Although humans being humans, there are obstacles even to successful iodization programs3.)

Cretinism is only the most extreme form of iodine deficiency, although a major & worthwhile humanitarian task; iodine correlates with IQ in non-deficient children, eg. Japan is simultaneously one of the longest-lived & highest IQ countries in the world and one of the greatest consumers of iodine4 (from seaweed, principally, levels so high they suggest that current recommendations are overly conservative), and even weak hypothyroidism impairs mental performance (in the old). School is directly impacted in randomized trials; from a review of Poor Economics (2011):

Providing iodine capsules to pregnant mothers is an intervention that helps brain development in fetuses. It costs around 51 cents per dose—and leads to kids who stay in school about five months longer because they are cognitively better able to learn.

The original waves of iodization caused large-scale changes in: numbers of people going to school5, working at all6, their occupation7, how they voted, or even how many recruits from a region are accepted to selective flight schools8.

Of course, iodine can be a double-edged sword. et al 2008 mentioned a wave of disorders after iodization of salt, as long-deficient thyroids were shocked with adequate levels of iodine, and natural iodine levels can be so high as to begin to inversely correlate with IQ in China.9

More worrisome is recent trends in the developed world such as the War on Salt. Un-iodized salt or low-iodide salt like sea salt is ever more popular. Existing iodized table salt often has far less iodide than recommended, or even what the manufacturer claims it has10. Iodized salt used in cooking—as opposed to a straight table-side condiment—loses large chunks of its iodine content11. Small samples of ordinary people turn in severe or mild iodine deficiency rates of 67%12 to as much as 73.7%13. This is plausible given a steady secular trend of iodine reduction in the US (although one that seems to have paused in the 2000s)14. I was unsurprised to read 2012:

Numerous population studies from a variety of countries including China, Hong Kong, Iran, India, Kyrgyzstan and England have reported iodine deficiency in girls of child bearing age 76, in pregnant 154,155,156,157, and in pregnant and lactation women 158,159. Some of these studies included regions where salt iodization is practiced, yet a [substantial] proportion of pregnant and lactating women were still deficient 155,156,157,158,159,160,161. A few examples of recent studies follow…

This has led to an observable impact on the IQ of the children of English women ( et al 2013), and there is no reason to expect the effect to be confined to them.

Meta-Analysis

Given all this, one naturally wonders what the effect might be in older humans: elementary school age and above. If iodine before birth can be responsible for increasing IQ by a full standard deviation or more in combination with iron, what about iodine post-birth? Iron supplementation treats anemia and there is evidence it also treats the cognitive problems as well, so what about iodine?

et al 2009, and tangential results like Bongers- et al 2005 (where there was a discernible IQ difference between TSH treatment of infants with congenital hypothyroidism before & after 13 days post-birth) suggest that the window for iodine intervention may close rapidly during pregnancy and be closed post-birth. While iodine has been extensively studied in infants and other unusual populations, the narrow question of iodine’s effect on IQ in healthy adult First World populations has not been (a common problem in nootropics); we are interested in cases only where someone is mentally tested before and after iodine supplementation, or where 1 cohort receives supplementation after birth when compared against a similar cohort who receive no supplementation. Most studies turn out to be either correlational (eg. stratifying by blood levels of thyroid hormone) or comparing fetal supplementation against a non-supplemented control group. Unfortunately, no study is so large and high-quality that it definitively resolves our question. So we resort to meta-analysis of what is available: we pool many studies together to derive a summary average of the overall results, weighted by how many subjects each study had (since more is better) versus how strong a result they yielded. An example of this is the meta-analysis & review, which is the closest existing study to what I want, “Iodine and Mental Development of Children 5 Years Old and Under”:

Several reviews and meta-analyses have examined the effects of iodine on mental development. None focused on young children, so they were incomplete in summarizing the effects on this important age group. The current systematic review therefore examined the relationship between iodine and mental development of children 5 years old and under. A systematic review of articles using MEDLINE (1980-November 201115ya) was carried out. We organized studies according to four designs: (1) randomized controlled trial with iodine supplementation of mothers; (2) non-randomized trial with iodine supplementation of mothers and/or infants; (3) prospective cohort study stratified by pregnant women’s iodine status; (4) prospective cohort study stratified by newborn iodine status. Average effect sizes for these four designs were 0.68 (2 RCT studies), 0.46 (8 non-RCT studies), 0.52 (9 cohort stratified by mothers’ iodine status), and 0.54 (4 cohort stratified by infants’ iodine status). This translates into 6.9 to 10.2 IQ points lower in iodine deficient children compared with iodine replete children. Thus, regardless of study design, iodine deficiency had a substantial impact on mental development. Methodological concerns included weak study designs, the omission of important confounders, small sample sizes, the lack of cluster analyses, and the lack of separate analyses of verbal and non-verbal subtests. Quantifying more precisely the contribution of iodine deficiency to delayed mental development in young children requires more well-designed randomized controlled trials, including ones on the role of iodized salt.

But its second design conflates supplementation of mothers with that of infants & children, and so the d = 0.46 (figure 2) is not directly meaningful (the authors note that the studies are heterogeneous but do not attempt stratifying by fetal vs infancy). More relevant is “Effect of iodine supplementation in pregnancy on child development and other clinical outcomes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials”, et al 2013:

…Fourteen publications that involved 8 trials met the inclusion criteria. Only 2 included trials reported the growth and development of children and clinical outcomes. Iodine supplementation during pregnancy or the periconceptional period in regions of severe iodine deficiency reduced risk of cretinism, but there were no improvements in childhood intelligence, gross development, growth, or pregnancy outcomes, although there was an improvement in some motor functions. None of the remaining 6 RCTs conducted in regions of mild to moderate iodine deficiency reported childhood development or growth or pregnancy outcomes. Effects of iodine supplementation on the thyroid function of mothers and their children were inconsistent.

They correctly observe that the available studies are not very methodologically rigorous and most do not allow of any real analysis, but I think it may be worth doing a more permissive summary and see what it says. et al 2014’s “Impact of iodine supplementation in mild-to-moderate iodine deficiency: systematic review and meta-analysis” looks at Gordon & Zimmerman, combining the available tests and finding:

For the meta-analysis cognitive tests were categorized into the following domains: (i) perceptual reasoning; (ii) processing speed; (iii) working memory; and (iv) global cognitive index. The global cognitive index was derived from the average of the scores in each of the domains. Unadjusted SMDs of the change in cognitive scores from baseline were computed from the raw scores reported by the authors, while adjusted SMDs were derived from the reported mean-adjusted treatment effects. s.e.m.-adjusted treatment effects were calculated using the recommended formula in the Cochrane handbook (44). The results of the analysis for individual domains are presented in Table 3, while Fig. 3 shows the forest plots for the global cognitive index. Beneficial effects of iodine supplementation were seen for both adjusted and unadjusted global indices with mild heterogeneity observed between the studies. For individual unadjusted domain scores, benefits were seen for processing speed but not for perceptual reasoning or working memory, while for the adjusted domains iodine was beneficial for perceptual reasoning although this was associated with significant heterogeneity.

Possible Studies

I have looked at the following studies:

“Neurological damage to the fetus resulting from severe iodine deficiency during pregnancy”, et al 1971; “The effect of iodine prophylaxis on the incidence of endemic cretinism”, et al 1972; “Fetal iodine deficiency and motor performance during childhood”, et al 1979; “A controlled trial of iodinated oil for the prevention of endemic cretinism: a long-term follow-up”, 1987; a 196660ya Papua New Guinea trial which in 197254ya began supplementing the control group as well (who were now 0–6 years old); at the 198244ya followup, the control group still suffered cretinism and deficits compared to the experimental—no effect. These studies turn out to not test the adults or children born before iodization and so are not useful for our purpose.

“Prophylaxis of endemic goiter with iodized oil in rural Peru”, et al 1972; “Iodine deficiency and the maternal-fetal relationship”, et al 1974 (see also the retrospective review 1994): a 196660ya Peru trial; females (<45 years old) and males (<18 years old); experimental infants did not outperform control infants—no effect. These studies turn out to not test the adults or children born before iodization and so are not useful for our purpose.

“The effects of oral iodized oil on intelligence, thyroid status, and somatic growth in school-age children from an area of endemic goiter”, Bautista et al. A 198244ya Bolivia trial; 200 schoolchildren measuring IQ—no effect

“Supplementary iodine fails to reverse hypothyroidism in adolescents and adults with endemic cretinism”, et al 1990; 28 Chinese aged 14–52, severely deficient, with no gains on the “Hiskey Nebraska Test of Learning Aptitude” or the “Griffiths Mental Development Scales”—no effect

“Controlled trial of vitamin-mineral supplementation: Effects of intelligence and performance”, et al 1991; multivitamin with 0.075mg iodine, IQ gain in the 8th and 10th graders—beneficial effect

“Timing of Vulnerability of the Brain to Iodine Deficiency in Endemic Cretinism”, et al 1994: 689 children 0–3 years of age, minimal effect in the children

“Dietary intake and micronutrient status of adolescents: effect of vitamin and trace element supplementation on indices of status and performance in tests of verbal and non-verbal intelligence”, et al 1994: 13–15 year olds with a multivitamin of things including iodine (0.15mg); no effect on IQ test

“Improved iodine status is associated with improved mental performance of schoolchildren in Benin”, van den et al 2000; originally a double-blind RCT, but subjects were contaminated by importation of iodized salt (there was an apparent small-medium effect on the matrix subtest)

“Cognitive and motor functions of iodine-deficient but euthyroid children in Bangladesh do not benefit from iodized poppy seed oil (Lipiodol)”, et al 2001: 1st and 2nd grade children, ~1mg? no effect

“Influence of supplementary vitamins, minerals and essential fatty acids on the antisocial behavior of young adult prisoners”, et al 2002: over 18 prisoners, 0.14mg; beneficial effect on measures of violence, but they did not do an intelligence retest and so are not useful for our purpose.

“Effects of iodine supplementation during pregnancy on child growth and development at school age”, 2002; included children who were supplemented at age 2 but only tested with Raven’s at age 7, which renders their data not useful. However, the general results confirm that timing of supplementation even within pregnancy follows the ‘earlier is better’ rule.

“Iodine supplementation improves cognition in iodine-deficient schoolchildren in Albania”, et al 2006

“Effect of multivitamin and multimineral supplementation on cognitive function in men and women aged 65 years and over: a randomized controlled trial”, et al 2007; old adults, 0.15mg; no effect

“Delayed Neurobehavioral Development in Children Born to Pregnant Women with Mild Hypothyroxinemia During the First Month of Gestation: The Importance of Early Iodine Supplementation”, et al 2009; turns out that supplementation was administered to all women during their pregnancy, so the development scores are not useful here.

“Iodine supplementation improves cognition in mildly iodine-deficient children”, et al 2009

think2 project:

“The effect of iodine supplementation on cognition of mildly iodine deficient young New Zealand adults”, 2012 (see also the presentation abstract of this as et al 2012): Young adults (“18–30 years”), 33.6mg total dose; no effect. (The paper should be available in “late” 201214ya, according to Fitzgerald, but remains unavailable as of 2015-02-26.)

“Iodine and Cognition in Young Adults: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial”, 2011; both Fitzgerald & Redman are reporting on the “think2” project, and the descriptions & figures reported are consistent with each other, so it seems the think2 results have been reported in separate theses.

et al 2012, “Iodine supplementation into drinking water improved intelligence of preschool children aged 25–59 months in Ngargoyoso sub-district, Central Java, Indonesia: A randomized control trial”; subjects selected for low urinary iodine excretion, region has >50% goiter rates

“Timing of the Effect of Iodine Supplementation on Intelligence Quotients of Schoolchildren”, et al 2004; followup in 2 Iranian villages after the national institution of iodization in 1989

1999, Use of Oral Iodized Oil to Control Iodine Deficiency in Indonesia, chapter 4 “Effect of stunting, iodine deficiency and oral iodized oil supplementation on cognitive performance of school children in an endemic iodine deficient area of Indonesia”, pg69–87

Fierro- et al 1972 & Fierro- et al 1974, which are followups to the intervention reported in Fierro- et al 1968 & et al 1969 (for a review of the Ecuadorian experiments, see 1994); a groundbreaking series of studies beginning in the 1960s in which 8 goiterous villages in Ecuador were treated with iodine injections and subsequent long-term outcomes measured through to the 1980s; for the most part, studied children were affected prenatally

et al 1995, “A randomized trial for the treatment of mild iodine deficiency during pregnancy: maternal and neonatal effects”: pregnant women only, no cognitive measures

et al 1996, “Earliest prevention of endemic goiter by iodine supplementation during pregnancy”: ditto

et al 1993, “Amelioration of some pregnancy-associated variations in thyroid function by iodine supplementation”: ditto

et al 2013, “Providing lipid-based nutrient supplements does not affect developmental milestones among Malawian children”: intervention included iodine (90mcg per 150g container), but the development milestones are too different from IQ or cognition to use for this

et al 2013, “Infant neurocognitive development is independent of the use of iodised salt or iodine supplements given during pregnancy”: pregnancy only

et al 2015, “Out of Africa: Human Capital Consequences of In Utero Conditions”: an analysis of an intriguing natural experiment, “Operation Solomon”, in which 14k Ethiopians (the entire Ethiopian Jewish community) were over 2 days airlifted from Ethiopia to Israel and settled there. Since a fair number of the women were at varying stages of pregnancy, the abruptness & comprehensiveness of the relocation means that the causal effect of better Israeli prenatal care can be inferred without any of the usual confounders which would defeat an attempt to compare Ethiopian school or test scores with Israeli. They find large effects, especially for those airlifted during the first trimester of pregnancy & for females (which is consistent with the running theme of iodine studies: that the benefits are largest when done early during pregnancy and larger for females than males). Unfortunately, it can’t be included as the design is too different, nothing similar to IQ tests were administered, and the effects reflect all the factors entailed in moving to Israel, which highly likely goes well beyond just a multivitamin.

et al 2015, “The Effects of Six-Month L-Thyroxine Treatment on Cognitive Functions and Event-Related Brain Potentials in Children with Subclinical Hypothyroidism”: non-randomized

et al 2016, “Effects of maternal and child lipid-based nutrient supplements on infant development: a randomized trial in Malawi”: randomized, and includes children 6–18mo, but assessed only on development at 18mo, which can’t be considered a useful IQ test

et al 2015, “Prenatal Micronutrient Supplementation Is Not Associated with Intellectual Development of Young School-Aged Children”: 3 experimental groups: folate, folate+iron, folate+iron+others+150.0mg/d iodine, allowing a comparison of folate with folate+multivitamin; but only prenatal intervention was done.

et al 2016, “Fortified Iodine Milk Improves Iodine Status and Cognitive Abilities in Schoolchildren Aged 7–9 Years Living in a Rural Mountainous Area of Morocco” (followup to et al 2015): relevant

“A cluster-randomized, controlled trial of nutritional supplementation and promotion of responsive parenting in Madagascar: the MAHAY study design and rationale”, et al 2016: preregistration of a study protocol for a Madagascar study; daily 90μg iodine in the lipid-based T2/T3 arms vs T0/T1/T4 for children aged 6–18 months, developmental outcomes “Ages and Stages Questionnaire: Inventory” & “Bayley Scale” but no IQ test-analogue.

“Effect of iodine supplementation during pregnancy on thyroid function and cognitive development of offspring”, Jaiswal (Bangalore India): pregnant only, no IQ tests

et al 2003, “Effect of a multiple-micronutrient-fortified fruit powder beverage on the nutrition status, physical fitness, and cognitive performance of schoolchildren in the Philippines”: RCT in Philippine school-children (mean age 9.9); 4 groups total (fortified supplement x deworming), 10.8mg total iodine delivered over 16 weeks; Primary Mental Abilities Test for Filipino Children (PMAT-FC) used to measure cognitive performance

et al 2009, “Impact of milk consumption on performance and health of primary school children in rural Vietnam”: claims cognitive benefits, especially to short-term memory, but paper does not report quantitative results

et al 2016, “Effects of pre- and post-natal lipid-based nutrient supplements on infant development in a randomized trial in Ghana” & Adu- et al 2016, “Small-quantity, lipid-based nutrient supplements provided to women during pregnancy and 6 mo postpartum and to their infants from 6 mo of age increase the mean attained length of 18-mo-old children in semi-urban Ghana: a randomized controlled trial”: measured “motor, language, socio-emotional, and executive function at 18 months” but too early for valid IQ tests, and the children appear to have received supplementation pre-natally

Zhou et al, “The effect of iodine supplementation in pregnancy on early childhood neurodevelopment and clinical outcomes: results of an aborted randomized placebo-controlled trial”: pregnancy only

2017, “Iodine Supplementation for Premature Infants Does Not Improve IQ”: Bayley-III cognitive tests at age 2, no statistically-significant difference or trend for the iodine-supplemented children (30 μg⧸kg⧸day for >3 weeks; premature infants can weigh anywhere 0.5—2.5kg) . While the supplementation is post-pregnancy, premature infants are an unusual enough patient population (and one which frequently exhibits intellectual disability or other cognitive issues) that it probably is not a good idea to meta-analyze it with RCTs on normal children & adults.

et al 2014/ et al 2017, “Consumption of a Double-Fortified Salt Affects Perceptual, Attentional, and Mnemonic Functioning in Women in a Randomized Controlled Trial in India”: RCT of iron+iodine supplement in 18–55yo, but where the control also received iodized salt and the large benefits were due to reducing anemia

“Cognitive Consequences Of Iodine Deficiency In Adolescence: Evidence From Salt Iodization In Denmark”, 2019; natural experiment using the Danish government’s legalization of and then requirement to iodize salt, 1998–200125ya, with a difference-in-differences analysis suggesting d = 0.06 on affected adolescents’ high school GPA. (Not a RCT, and difference-in-differences are one of the weaker natural experiment designs.)

My above searches & review turned out to be partially redundant with a review that was published online a few months afterwards, in June 201214ya: Zimmerman’s “The Effects of Iodine Deficiency in Pregnancy and Infancy” and also his earlier 200917ya “Iodine deficiency in pregnancy and the effects of maternal iodine supplementation on the offspring: a review”. Regardless, the above was still useful because Zimmerman’s focus was not on any childhood or adult effects but the pregnancy & infancy effects. I have also benefited from “Iodine intake in human nutrition: a systematic literature review”. Finally, “Impact of iodine supplementation in mild-to-moderate iodine deficiency: systematic review and meta-analysis” ( et al 2014) reviews iodine studies and for cognitive performance, meta-analyzes et al 2009 & et al 2009, finding benefits.

Unfortunately, a few of the useful studies also tested a variety of substances, so any estimate of iodine’s effect size (such as it is) would be an overestimate: the iodine might be synergizing with one of the other ingredients (eg. iron or selenium) or the iodine might not be the responsible agent at all! We will code that covariate in. But what implications can we draw out via a meta-analysis?

Data

First, the data from the surviving studies:

study |

group |

year |

n.e |

mean.e |

sd.e |

n.c |

mean.c |

sd.c |

age |

dose |

multi |

country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bautista |

Bautista |

1982 |

100 |

69.43 |

10.96 |

100 |

70.31 |

10.96 |

8.75 |

475 |

0 |

Bolivia |

Boyages |

Boyages |

1990 |

28 |

34.4 |

15.4 |

24 |

29.5 |

8.5 |

29.5 |

720 |

0 |

China |

Schoenthaler.1 |

Schoenthaler |

1991 |

100 |

10.1 |

8.9 |

33.3 |

8.9 |

7.3 |

14 |

12.68 |

1 |

USA |

Schoenthaler.2 |

Schoenthaler |

1991 |

105 |

12.6 |

7.9 |

33.3 |

8.9 |

7.3 |

14 |

25.35 |

1 |

USA |

Schoenthaler.3 |

Schoenthaler |

1991 |

105 |

10.4 |

7.6 |

33.3 |

8.9 |

7.3 |

14 |

25.35 |

1 |

USA |

Southon |

Southon |

1994 |

22 |

63.94 |

2.6 |

29 |

64.1 |

1.87 |

13.5 |

16.8 |

1 |

UK |

Shrestha.1 |

Shrestha |

1994 |

72 |

17.1 |

1.8 |

36 |

10.7 |

2.4 |

7.1 |

490 |

0 |

Malawi |

Shrestha.2 |

Shrestha |

1994 |

80 |

18.2 |

1.5 |

36 |

10.7 |

2.4 |

7.1 |

490 |

0 |

Malawi |

Isa |

Isa |

2000 |

60 |

85.25 |

14.6 |

100 |

83.6 |

16.2 |

11.39 |

480 |

0 |

Malaysia |

Huda |

Huda |

2001 |

145 |

14.88 |

3.28 |

142 |

14.60 |

3.19 |

9.8 |

400 |

0 |

Bangladesh |

Zimmerman |

Zimmerman |

2006 |

159 |

25 |

6.3 |

151 |

20.5 |

5.6 |

11 |

400 |

0 |

Albania |

McNeill |

McNeill |

2007 |

398 |

11.5 |

2.3 |

374 |

11.7 |

2.1 |

72 |

54.75 |

1 |

UK |

Gordon |

Gordon |

2009 |

84 |

10.2 |

3 |

82 |

9.6 |

2.4 |

11.5 |

29.4 |

0 |

NZ |

Dewi |

Dewi |

2012 |

33 |

110.27 |

9.04 |

34 |

103.06 |

9.99 |

3.1 |

8.4 |

0 |

Indonesia |

Salarkia |

Salarkia |

2004 |

19 |

96 |

10 |

246 |

89 |

13 |

1.5 |

1272 |

0 |

Iran |

Untoro |

Untoro |

1999 |

121 |

89 |

7 |

43 |

88 |

6 |

9 |

464 |

0 |

Indonesia |

Redman |

Redman |

2011 |

86 |

20.85 |

3.43 |

86 |

20.59 |

3.27 |

21.28 |

45 |

0 |

NZ |

Solon |

Solon |

2003 |

412 |

1.82 |

0.22 |

419 |

1.66 |

0.22 |

9.9 |

10.752 |

1 |

Philippines |

Comments:

“age” variable is based on a simple average age in years of subjects (unweighted) or the reported mean; “dose” is total administered iodine in milligrams (note that studies typically report in micrograms/μg per day or week); multi is whether the study used solely iodine (0) or other chemicals such as iron (1)

Bautista notes: Stanford-Binet IQ, some data re-derived15

Boyages: the two groups were not randomly chosen and may have pre-existing differences in IQ

Schoenthaler: RAPM IQ

Cao: an earlier version of this meta-analysis used its “developmental quotient” excluding the pregnant women’s offspring; since this does not seem to be IQ, I removed it

Southon: Non-verbal IQ scores pooled16

McNeill: Digit span used in place of IQ scores (WM correlates highly with IQ)

Gordon: score from matrix subtest (1 of 4 subtest scores; 2 showed positive trend but not significance)

Manger: earlier version used Manger’s backwards digit span (backwards is a WM test which loads on g); however, the meta-analysis Melby-2013 & my own n-back meta-analysis found that WM exercises which transferred to digit spans did not also transfer to IQ tests, raising questions about using digit span as a proxy for IQ in a causal rather than correlational analysis

Stuijvenberg: see Manger

Isa: IQ scores reported in unhelpful format; means & deviations reverse-engineered from percentile distribution17; as usual, pregnancy-related scores are omitted

Shrestha: ‘Fluid intelligence’ scores reported, omitting ‘Crystallized intelligence’ & ‘Perceptual skill’; the control group is split across the iodine intervention (“Shrestha.1”) and the iodine+iron intervention (“Shrestha.2”)

Salarkia:

the paper’s original control group using contemporary age/sex-matched Tehran children, doesn’t account for their superior IQ scores and likely superior SES; I have instead used the reported 198937ya IQ scores of the previous generation of children

the administered iodine includes the 480mg from iodized oil but also the 6 years of iodized salt consumption (40mg⧸kg, national daily per capita average salt consumption 9g or 132mg a year) for a total of 1272mg

Untoro: there were 3 dose groups (200/400/800mg) but Untoro reported summary statistics for the iodine group as a whole:

The urinary iodine concentration and thyroid volume of all treatment groups were [statistically-]significantly improved after the supplementation, but there were no differences among the supplemented groups in cognitive performance. Therefore we combined the three iodized oil supplemented groups into one group.

The listed dose is a weighted average.

Redman: dose is calculated as: 150 μg, 100 pills a bottle, 3 bottles (1 initial bottle, 2 replacements in mail) = 150 × 100 × 3 = 45000μg; scores are from the Matrix Reasoning subtest

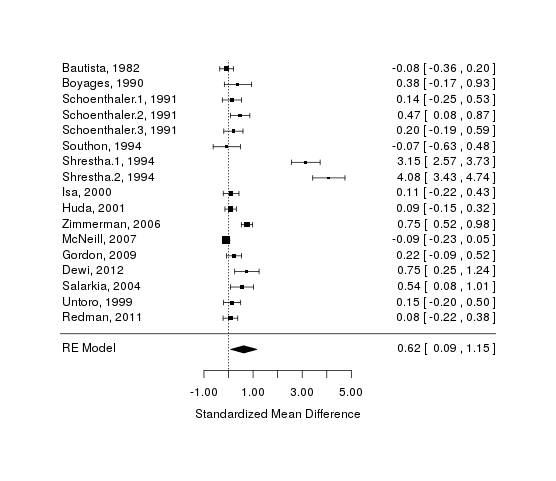

The result of the meta-analysis:

Random-Effects Model (k = 17; tau^2 estimator: REML)

tau^2 (estimated amount of total heterogeneity): 1.2100 (SE = 0.4432)

tau (square root of estimated tau^2 value): 1.1000

I^2 (total heterogeneity / total variability): 97.87%

H^2 (total variability / sampling variability): 47.02

Test for Heterogeneity:

Q(df = 16) = 285.8785, p-val < .0001

Model Results:

estimate se zval pval ci.lb ci.ub

0.6204 0.2716 2.2844 0.0223 0.0881 1.1527Test for Heterogeneity:

Q(df = 16) = 285.8785, p-val < .0001

Model Results:

estimate se zval pval ci.lb ci.ub

0.2565 0.0380 6.7536 <.0001 0.1820 0.3309So the effect size is, as expected, small: d = 0.2. A far cry from the d > 1 which we might estimate from the prenatal studies.

The large difference in d—0.2 vs 0.6—between the fixed-effects and random-effects models is concerning. Given the extremely high heterogeneity of the i2, which indicates that there are large differences between some of the studies, a random-effects is more appropriate in principle; but further analysis shows this is being driven by a far outlier of Shrestha, and so I believe the fixed-effects estimate of 0.2 winds up being more accurate.

A pretty forest plot summary:

A forest plot of iodine studies

Moderators

Age & Dose

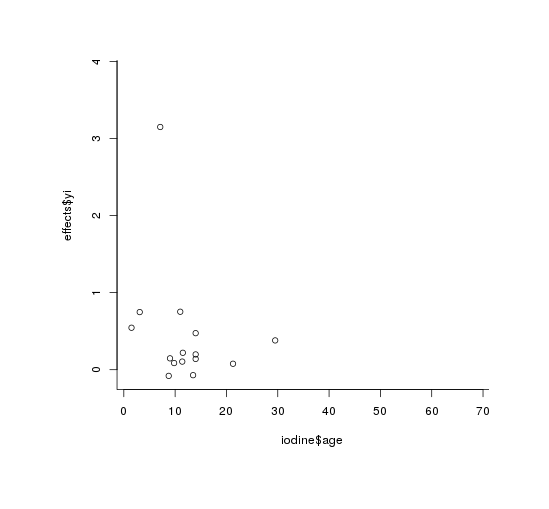

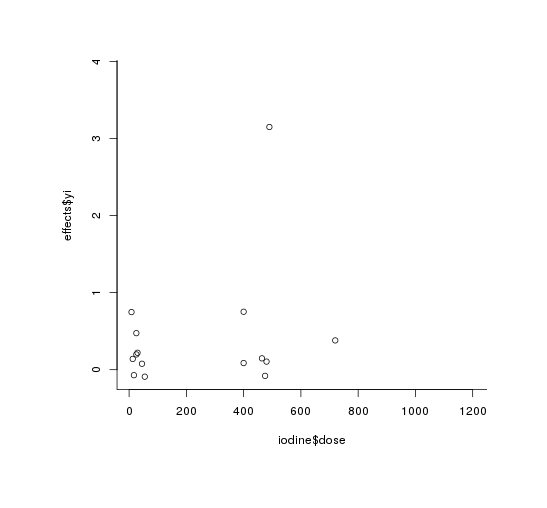

We suspected, based on the equivocal results in post-birth studies and the large decline in effect over the duration of a pregnancy in the Chinese studies, that if there was any benefit, it would be in the young; on the same reasoning, we might expect large doses to do more good than smaller ones. The necessary data is encoded into the table already, so we run a meta-analytic regression on them as independent predictors:

tau^2 (estimated amount of residual heterogeneity): 1.2521 (SE = 0.4902)

tau (square root of estimated tau^2 value): 1.1190

I^2 (residual heterogeneity / unaccounted variability): 97.49%

H^2 (unaccounted variability / sampling variability): 39.92

R^2 (amount of heterogeneity accounted for): 0.00%

Test for Residual Heterogeneity:

QE(df = 14) = 243.6469, p-val < .0001

Test of Moderators (coefficient(s) 2,3):

QM(df = 2) = 1.6083, p-val = 0.4475

Model Results:

estimate se zval pval ci.lb ci.ub

intrcpt 0.6793 0.5205 1.3053 0.1918 -0.3407 1.6994

iodine$age -0.0157 0.0183 -0.8568 0.3915 -0.0515 0.0202

iodine$dose 0.0006 0.0009 0.6665 0.5051 -0.0011 0.0023The coefficients and variability are disappointing: the age and dose moderators explain little of what is going on.

Some graphs to help us visualize. Graphing by age, we see what might be a slight negative relationship, as the regression suggests (driven by 1994):

plot(iodine$age, effects$yi)

Graphing by dose, we see—despite the calculated statistical-significance—no relationship at all to my eyes (outliers are 1994, again):

plot(iodine$dose, effects$yi)

The estimate is the important part: neither of the moderators seem to have a strong relationship with the cognitive benefits (nor are they at least statistically-significant). It would seem that any effectiveness of iodine is unrelated to age and dose. Whether the effectiveness is being driven by a few studies is what we’ll look at next.

Multiple Supplements

One methodological concern is that by including studies like Southon which supplemented many things besides iodine, our results are merely picking up the efficacy of other supplements (iron is a particular concern). Curiously, despite our expectation that the multi-vitamin studies would have higher effect sizes because any of the ingredients could be helpful singly or synergistically, it is strikingly the opposite:

QM(df = 2) = 6.7027, p-val = 0.0350

Model Results:

estimate se zval pval ci.lb ci.ub

factor(iodine$multi)0 0.8250 0.3203 2.5756 0.0100 0.1972 1.4529

factor(iodine$multi)1 0.1300 0.4953 0.2625 0.7930 -0.8408 1.1008Bias Checks

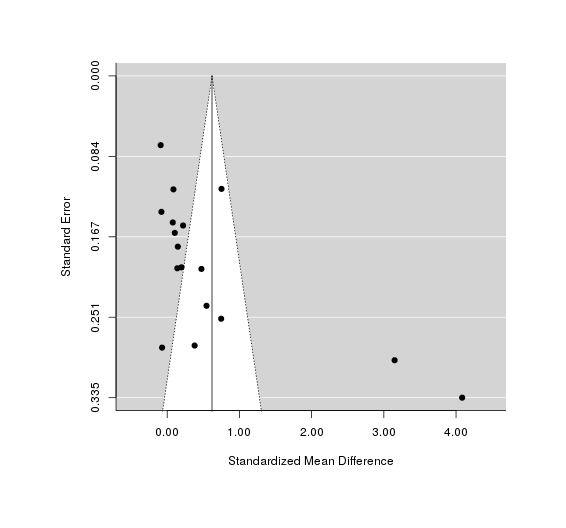

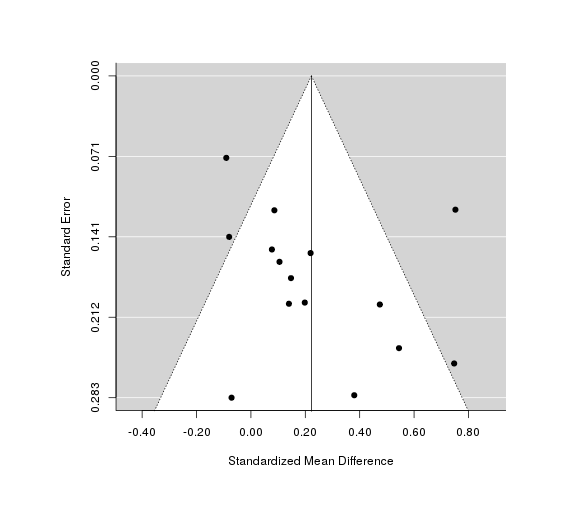

We do not have enough to reliably check for biases like publication bias, but we can still try. The funnel plot looks pretty bizarre, with almost all studies tightly bunched around the null effect but 2 outliers—the 2 1994 groups we just saw—showing shockingly high effect sizes of d = 3.1/4.1. Why did 1994 observe such large IQ effects? I don’t know, although the Malawi region was chosen for its iodine deficiency.

A test & graph:

test for funnel plot asymmetry: z = 3.3206, p = 0.0009

A funnel plot of effect size versus sample size, checking for bias in publishing only good-looking results on iodine

So 1994 is driving most of the effect! (Not a surprise at this point.) If we omit those points, the funnel plot is cleaner

A funnel plot with Shrestha removed, showing better fit from the weaker estimate.

A trim-and-fill check agrees with us and not the test, by deciding not to add in any new studies between Shrestha and the rest; we also notice that the τ2 & i2 are extremely high, which is just telling us what we know—1994 is different from the other studies:

Estimated number of missing studies on the left side: 0 (SE = NA)

Random-Effects Model (k = 17; tau^2 estimator: REML)

tau^2 (estimated amount of total heterogeneity): 1.2100 (SE = 0.4432)

tau (square root of estimated tau^2 value): 1.1000

I^2 (total heterogeneity / total variability): 97.87%

H^2 (total variability / sampling variability): 47.02If we were to redo the analysis but omitting 1994, we see a much smaller effect-size:

Random-Effects Model (k = 15; tau^2 estimator: REML)

tau^2 (estimated amount of total heterogeneity): 0.0526 (SE = 0.0313)

tau (square root of estimated tau^2 value): 0.2293

I^2 (total heterogeneity / total variability): 68.75%

H^2 (total variability / sampling variability): 3.20

Test for Heterogeneity:

Q(df = 14) = 53.0253, p-val < .0001

Model Results:

estimate se zval pval ci.lb ci.ub

0.2224 0.0751 2.9602 0.0031 0.0752 0.3697So, it seems a lot of the effect size is being driven by a few studies turning in large or extremely large effect sizes: Shrestha, Zimmerman, and Dewi (in chronological order). One common factor to these studies seems to be that they worked in the most iodine-deprived areas possible: Shrestha chose his region as being the worst he could find, and Dewi cites reports of goiter in half the population while targeting the supplementation to the most deficient children.

At most, we can justify an effect estimate which is much smaller than would be estimated based on the prenatal studies, and the reality of this residual effect can be doubted: looking at the forest plot, the more rigorous and Western studies seem to have the tiniest and closest to zero estimates.

Code

Run as R --slave --file=iodine.r:

set.seed(7777) # for reproducible numbers

# TODO: factor out common parts of `png` (& make less square), and `rma` calls

# install.packages("XML") # if not installed

library(XML)

iodine <- readHTMLTable(colClasses = c("character", "integer", rep("numeric", 8)),

"https://gwern.net#data")[[1]]

# install.packages("metafor") # if not installed

library(metafor)

effects <- escalc("SMD", m1i = mean.e, m2i = mean.c, sd1i = sd.e, sd2i = sd.c, n1i = n.e, n2i = n.c,

data = iodine)

cat("Basic random-effects meta-analysis of all studies:\n")

res1 <- rma(yi, vi, data = effects); res1

cat("Fixed-effects version:\n")

res2 <- rma(yi, vi, data = effects, method="FE"); res2

png(file="~/wiki/doc/iodine/gwern-iodization-forest.png", width = 480, height = 480)

forest(res1, slab = paste(iodine$study, iodine$year, sep = ", "))

invisible(dev.off())

cat("Random-effects with age & dose moderators:\n")

rma(yi, vi, mods = ~ iodine$age + iodine$dose, data = effects)

png(file="~/wiki/doc/iodine/gwern-age.png", width = 480, height = 480)

plot(iodine$age, effects$yi)

invisible(dev.off())

png(file="~/wiki/doc/iodine/gwern-dose.png", width = 480, height = 480)

plot(iodine$dose, effects$yi)

invisible(dev.off())

cat("Check random-effects meta-analysis for whether the multiple-supplement trials are inflating results:\n")

rma(yi, vi, mods = ~ factor(iodine$multi) - 1, data = effects)

png(file="~/wiki/doc/iodine/gwern-iodization-funnel.png", width = 480, height = 480)

funnel(res1)

invisible(dev.off())

cat("The funnel plot looks weird, test it:\n")

regtest(res1, model = "rma", predictor = "sei", ni = NULL)

cat("For kicks, what does a (normal) trim-and-fill say?\n")

tf <- trimfill(res1); tf

cat("Re-run random-effects meta-analysis, omitting Shrestha:\n")

res3 <- rma(yi, vi, data = escalc("SMD", m1i = mean.e, m2i = mean.c, sd1i = sd.e, sd2i = sd.c,

n1i = n.e, n2i = n.c,

data = iodine[!(grepl("Shrestha", iodine$study)),])); res3

# funnel plot with Shrestha omitted

png(file="~/wiki/doc/iodine/gwern-funnel-moderated.png", width = 480, height = 480)

funnel(res3)

invisible(dev.off())

# optimize the generated graphs by cropping whitespace & losslessly compressing them

system(paste('cd ~/wiki/image/iodine/ &&',

'for f in *.png; do convert "$f" -crop',

'`nice convert "$f" -virtual-pixel edge -blur 0x5 -fuzz 10% -trim -format',

'\'%wx%h%O\' info:` +repage "$f"; done'))

system("optipng -o9 -fix ~/wiki/image/iodine/*.png", ignore.stdout = TRUE)See Also

Iodine section of Nootropics essay -(motivation; some statistical power calculations for a self-experiment looking for cognitive improvement; a “value of information” calculation on the possible benefit versus the quality of information from self-experimenting; a silly eye-color experiment resulting in no change from supplementation)