Design Of This Website

Meta page describing Gwern.net, the self-documenting website’s implementation and experiments for better ‘semantic zoom’ of hypertext; technical decisions using Markdown and static hosting.

Gwern.net is implemented as a static website compiled via Hakyll from Pandoc Markdown and hosted on a dedicated server (due to expensive cloud bandwidth).

It stands out from your standard Markdown static website by aiming at good typography, fast performance, and advanced (ie. 1980s-era) hypertext browsing features (at the cost of great implementation complexity); the 4 design principles are: aesthetically-pleasing minimalism, accessibility/progressive-enhancement, speed, and a ‘semantic zoom’ approach to hypertext use.

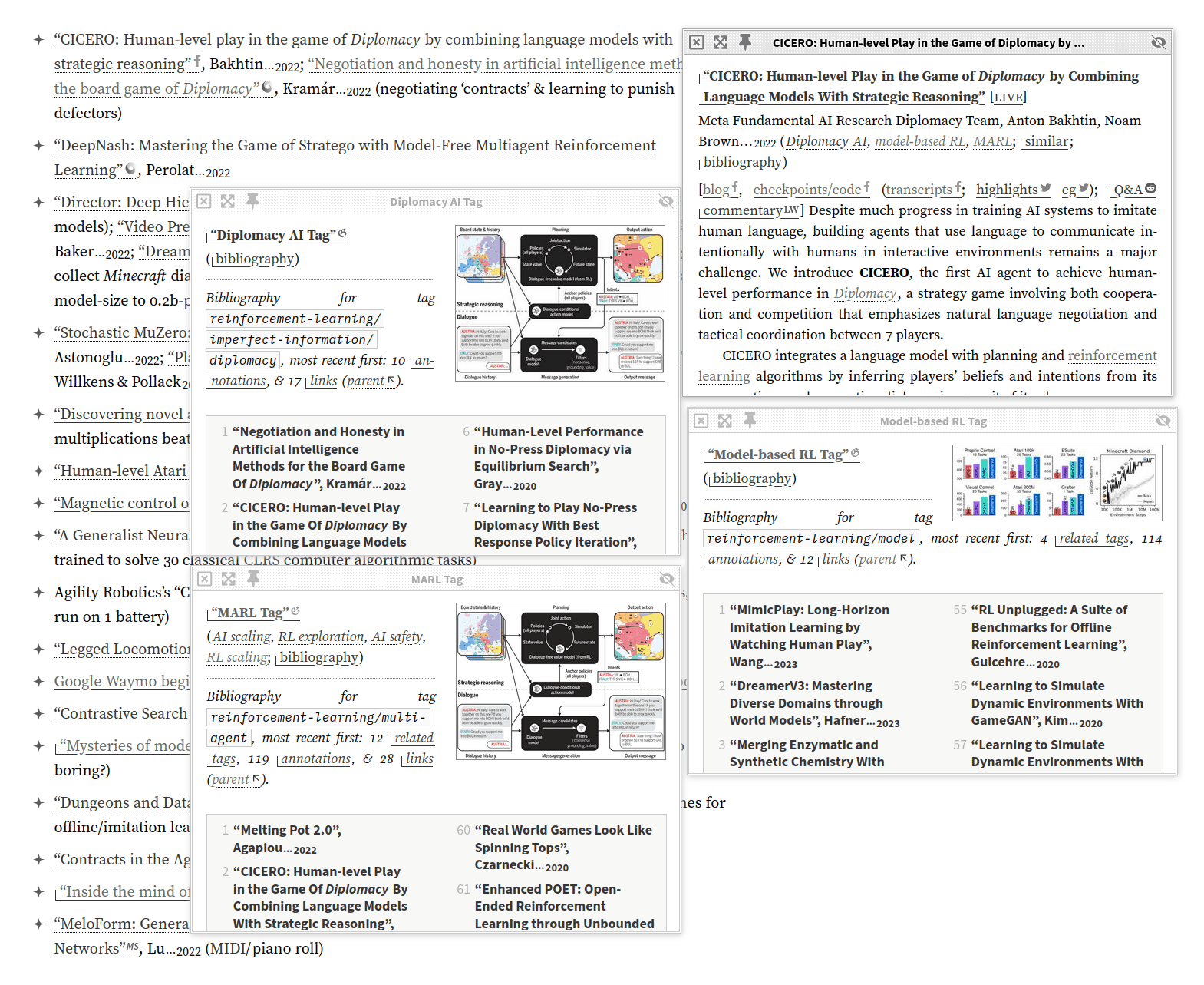

Unusual features include the monochrome esthetics, sidenotes instead of footnotes on wide windows, efficient dropcaps, smallcaps, collapsible sections, automatic inflation-adjusted currency, Wikipedia-style link icons & infoboxes, custom syntax highlighting, extensive local archives to fight linkrot, and an ecosystem of “popup”/“popover” annotations & previews of links for frictionless browsing—the net effect of hierarchical structures with collapsing and instant popup access to excerpts enables iceberg-like pages where most information is hidden but the reader can easily drill down as deep as they wish. (For a demo of all features & stress-test page, see Lorem Ipsum; for detailed guidelines, the Manual of Style.)

Also discussed are the many failed experiments/changes made along the way.

What does it take to present, for the long-term, complex, highly-referenced, link-intensive, long-form text online as effectively as possible, while conserving the reader’s time & attention?

Benefit

People who are really serious about software should make their own hardware.

Alan Kay, “Creative Think” 1982

Time well-spent.

The sorrow of web design & typography is that it all can matter just a little how you present your pages. A page can be terribly designed and render as typewriter text in 80-column ASCII monospace, and readers will still read it, even if they complain about it. And the most tastefully-designed page, with true smallcaps and correct use of em-dashes vs en-dashes vs hyphens vs minuses and all, which loads in a fraction of a second and is SEO optimized, is of little avail if the page has nothing worth reading; no amount of typography can rescue a page of dreck. Perhaps 1% of readers could even name any of these details, much less recognize them. If we added up all the small touches, they surely make a difference to the reader’s happiness, but it would have to be a small one—say, 5%.1 It’s hardly worth it for writing just a few things.

But the joy of web design & typography is that just its presentation can matter a little to all your pages. Writing is hard work, and any new piece of writing will generally add to the pile of existing ones, rather than multiplying it all; it’s an enormous amount of work to go through all one’s existing writings and improve them somehow, so it usually doesn’t happen. Design improvements, on the other hand, benefit one’s entire website & all future readers, and so at a certain scale, can be quite useful. I feel I’ve reached the point where it’s worth sweating the small stuff, typographically.

Principles

There are 4 design principles:

Aesthetically-pleasing Minimalism

The design esthetic is minimalist, with a dash of Art Nouveau. I believe that minimalism helps one focus on the content. Anything besides the content is distraction and not design. ‘Attention!’, as Ikkyu would say.2

The palette is deliberately kept to grayscale as an experiment in consistency and whether this constraint permits a readable aesthetically-pleasing website. Classic typographical tools, like dropcaps and small caps are used for theming or emphasis.3

This does not mean lacking features; many ‘minimalist’ designs proud of their simplicity are merely simple-minded.4

Accessibility & Progressive Enhancement

Semantic markup is used where Markdown permits. JavaScript is not required for the core reading experience, only for (mostly) optional features: popups & transclusions, table-sorting, sidenotes, and so on. Pages can even be read without much problem in a smartphone or a text browser like

elinks.Speed & Efficiency

On an increasingly-bloated Internet, a website which is anywhere remotely as fast as it could be is a breath of fresh air. Readers deserve better. Gwern.net uses many tricks to offer nice features like sidenotes or LaTeX math at minimal cost.

-

How should we present texts online? A web page, unlike many mediums such as print magazines, lets us provide an unlimited amount of text. We need not limit ourselves to overly concise constructions, which countenance contemplation but not conviction.

The problem then becomes taming complexity and length, lest we hang ourselves with our own rope. Some readers want to read every last word about a particular topic, while most readers want the summary or are skimming through on their way to something else. A tree structure is helpful in organizing the concepts, but doesn’t solve the presentation problem: a book or article may be hierarchically organized, but it still must present every last leaf node at 100% size. Tricks like footnotes or appendices only go so far—having thousands of endnotes or 20 appendices to tame the size of the ‘main text’ is unsatisfactory as while any specific reader is unlikely to want to read any specific appendix, they will certainly want to read an appendix & possibly many. The classic hypertext paradigm of simply having a rat’s-nest of links to hundreds of tiny pages to avoid any page being too big also breaks down, because how granular does one want to go? Should every section be a separate page? Every paragraph? (Anyone who attempted to read a GNU Info manual knows how tedious it can be.5) What about every reference in the bibliography, should there be 100 different pages for 100 different references?

A web page, however, can be dynamic. The solution to the length problem is to progressively expose more beyond the default as the reader requests it, and make requesting as easy as possible. For lack of a well-known term (Nelson’s “StretchText” never caught on) and by analogy to code folding in structural editors/outliners, I call this semantic zoom: the hierarchy is made visible & malleable to allow reading at multiple levels of the structure.

A Gwern.net page can be read at multiple structural levels, high to low: title, metadata block, abstracts, section headers, margin notes, emphasized keywords in list items, footnotes/sidenotes, collapsed sections or paragraphs, internal cross-referencing links to other sections (such as appendices) which popup for immediate reading, and fulltext links or internal links to other pages (also popping up).

So the reader can read (in increasing depth) the title/metadata, or the page abstract, or skim the headers/Table of Contents, then skim margin notes+item summaries, then read the body text, then click to uncollapse regions to read in-depth sections too, and then if they still want more, they can mouse over references to pull up the abstracts or excerpts, and then they can go even deeper by clicking the fulltext link to read the original. Thus, a page may look short, and the reader can understand & navigate it easily, but like an iceberg, those readers who want to know more about any specific point will find more under the surface.

Miscellaneous principles:

visual differences should be semantic differences

UI elements that can react should change on hover

all UI elements should have tooltips/summaries; interactive links should be either underlined or smallcaps

hierarchies & progressions should come in cycles of 3 (eg. bold > smallcaps > italics)

all numbers should be 0, 1, or ∞

function > form

more > less

self-contained > fragmented

convention (linters/checkers) > constraints

hypertext is a great idea, we should try that!

local > remote—every link dies someday

archives are expensive short-term but cheap long-term

reader > author

give the reader agency

speed is the 2nd-most important feature after correctness

you must earn your ornaments

if you go overboard on minimalism, you may barely be mediocre

UI consistency is underrated

when in doubt, copy Wikipedia

be as magical as Wikipedia was

if you find yourself doing something 3 times, fix it.

website content: good, FLOSS, unrestricted topic—choose two

A Title Is A Brand

Features

56. Software is under a constant tension. Being symbolic it is arbitrarily perfectible; but also it is arbitrarily changeable.

Notable features (compared to standard Markdown static sites):

link popup annotations (all types demo; ‘popover’ on small screens or mobile):

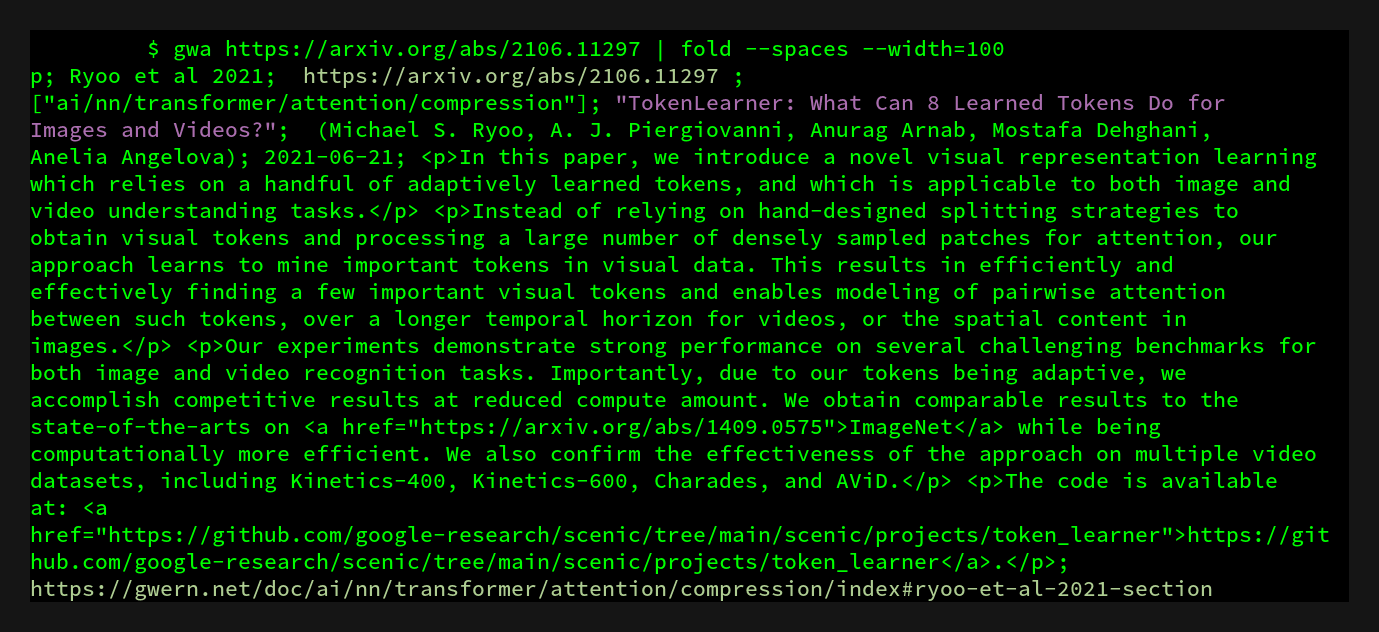

Annotations can be automatically extracted from sources (eg. Arxiv/BioRxiv/MedRxiv/Crossref), or written by hand (formatting is kept consistent by an extensive series of rewrite rules & checks, including machine learning to break up monolithic abstracts for readability); popups can be recursive, and can be manipulated in many ways—moved, fullscreened, ‘stickied’ (anchored in place), etc. Wikipedia pages are specially-supported, enabling them to be recursively navigated as well. Local Gwern.net pages & whitelisted domains can be popped up and viewed in full; PDFs can be read inside a PDF viewer; and supported source code formats can pop up syntax-highlighted versions (eg.

LinkMetadata.hs).client-side transclusion

Transclusion supports within-page or cross-page, arbitrary IDs or ranges in pages, links, annotations, etc. Transclusions are lazy by default, but can be made strict; this enables extremely large index pages, like the tags.

code folding-style collapse/disclosure support (both inline & block)

These are used heavily with lazy transclusions, as they let one create arbitrarily-large ‘virtual’ pages which are displayed on demand purely by writing ordinary hyperlinked text.

automatic local archive/mirrors of most links to eliminate linkrot from the start while providing a better reading experience

sidenotes using both margins, fallback to floating footnotes

margin notes (as inline or sidenotes)

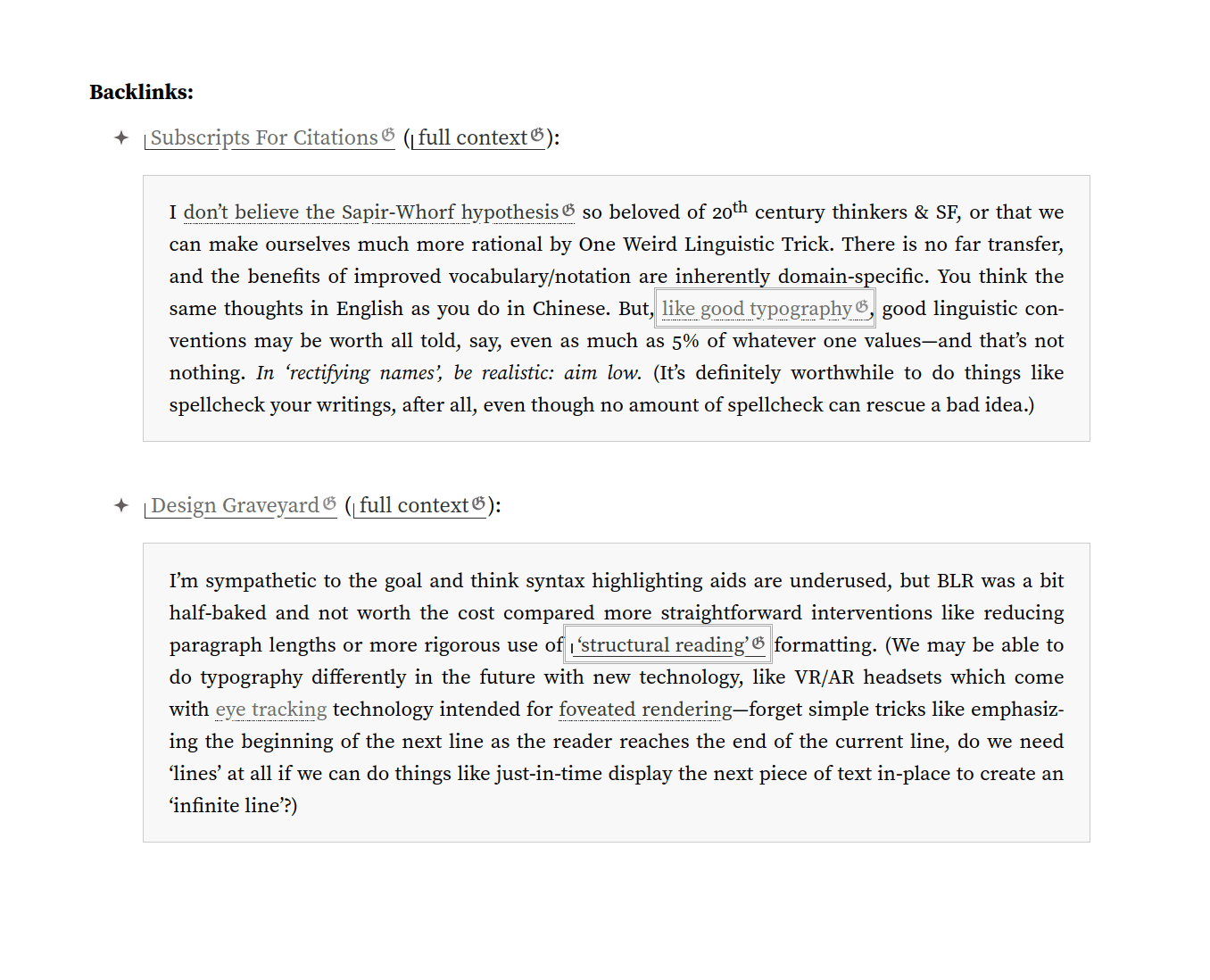

true bidirectional backlinks, which can pop up the context

also supported at the section level, so one can easily see discussions elsewhere of a specific part of a page, rather than the page as a whole

reader mode (alternative view removing most UX like hyperlinks, eg; toggle: )

source code syntax highlighting

using custom ALGOL-inspired monochrome theme

JavaScript-free LaTeX math rendering (examples; but where possible, it is compiled to native HTML+CSS+Unicode instead like “√4” or “1⁄2”, as that is more efficient & natural-looking)

dark mode (with a theme switcher and AI classification of whether to invert images using InvertOrNot.com)

click-to-zoom images & slideshows; width-full tables/images

sortable tables; tables of various sizes

automatically inflation-adjust dollar amounts, exchange-rate Bitcoin amounts (eg. ‘$1 in 1950 is $10.99$11950 today.’)

link icons for classifying links by filetype/domain/topic/author (examples; implementation background)

“admonitions” infoboxes (Wikipedia-like by way of Markdeep)

lightweight dropcaps

With support for AI-generated sets, like the “dropcats” used on cat-themed pages

advanced poetry support (concrete poetry, alliterative verse etc.)

multi-column lists

interwiki link syntax

automatic link-ification of keywords (LinkAuto.hs)

compact citation typesetting (using subscripts)

print support

epigraphs

blogroll implemented as “Site/quote/link of the day” in page footers

demo-mode: track the use-count of site features, in order to disable or change them after n uses.

This allows for obtrusive newbie-friendly features or appearances, which automatically simplify for regular readers. It is loosely inspired by classic electronics “demo mode” settings, which loop through all the features of a device. It uses LocalStorage to avoid any server integration.

We use it primarily to highlight the existence of the theme switcher toolbar (), so readers know how to enable the other features like dark-mode or reader-mode: the animation would be highly distracting if we ran it on every page load, but if we don’t how do readers discover it? (We’ve found out that a lot of readers do not notice it on their own, probably due to general web-clutter-blindness.) Our solution: we simply use demo-mode to disable it after a few times.

We also use it to slim down the UI. For example, the disclosure/collapse regions are unusual, so we write out a description explicitly for new readers; but they are so widely used that leaving the description in place is a lot of clutter for readers who have learned them.

404 page: a 404 error page uses the error, and sitemap + Levenshtein distance, to try to guess the intended URL, as well as pointing to the main index and providing site-search shortcuts.

(It also includes a curated selection of epigraphs & illustrations for the reader depressed by linkrot.)

Much of Gwern.net design and JavaScript/CSS was developed by Said Achmiz, 2017–202?. Some inspiration has come from Tufte CSS & Matthew Butterick’s Practical Typography.

Backlink

Gwern.net implements “bidirectional” hyperlinks6 or backlinks (eg. this page): links are both forwards (the normal kind) from the current page outwards to another; but also backwards, showing where on other pages is the current page linked.

Its backlinks are especially good because popups provide frictionless navigation; and our careful implementation means they can be provided in-context near the referenced content, and even between arbitrary URLs (via annotations).

Examples can be seen on Wikipedia or Andy Matuschak’s notes or increasingly popularized by Zettelkasten-esque services like Roam or Notion, and have a long history in hypermedia systems dating back at least to the initial schemes of Project Xanadu ~1965 (which also introduced transclusion, which we use extensively for the UI and to display said backlinks).

On Gwern.net, the backlinks for a page/annotation (and all anchors/IDs on it) are provided as a transcluded collapsed appendix at the bottom of each item. These sections list each backlink, and in addition, transclude the source of that backlink:

eg. for this page, one can see allusion to the “semantic zoom” neologism as a more useful design concept, or a justification of dabbling in typographic novelties like subscript notation (another example).

Backlinks are also overloaded to provide bibliographies of an author’s works: the author link of an annotation (such as their homepage or biography or WP article) is itself an annotated link, therefore, its backlinks will include all of the author’s known links. For convenience, when the backlink is an author link, it is prioritized by sorting to the front of the backlinks list, so scrolling an author’s backlinks will show first their publications and only then mentions of them.

Backlink Features

In-Context

This is possible because the links are tracked by use of unique IDs in the HTML, so it is possible to easily identify exactly where in the other page you have been linked.7

This also means we can display these same backlink entries everywhere relevant. For example, if the backlink is to a section, we do not have to settle for simply a big list of page-wide backlinks, we can put that section’s backlinks inside that section for the reader’s convenience: you finish reading a section, and then you immediately see where else on Gwern.net it has been linked:

The section which contains the semantic zoom ID also includes the backlink for “semantic zoom” links, which the reader can uncollapse to read.

This should be possible with other backlink systems but Gwern.net is nearly unique in ‘inlining’ backlinks like this.8

(The analogous forward-link feature is the link-bibliography, which aggregates all the forward-links in order. However, there is little need for ‘in-context’ forward-links since the essay or annotation already provides that context.)

Popups

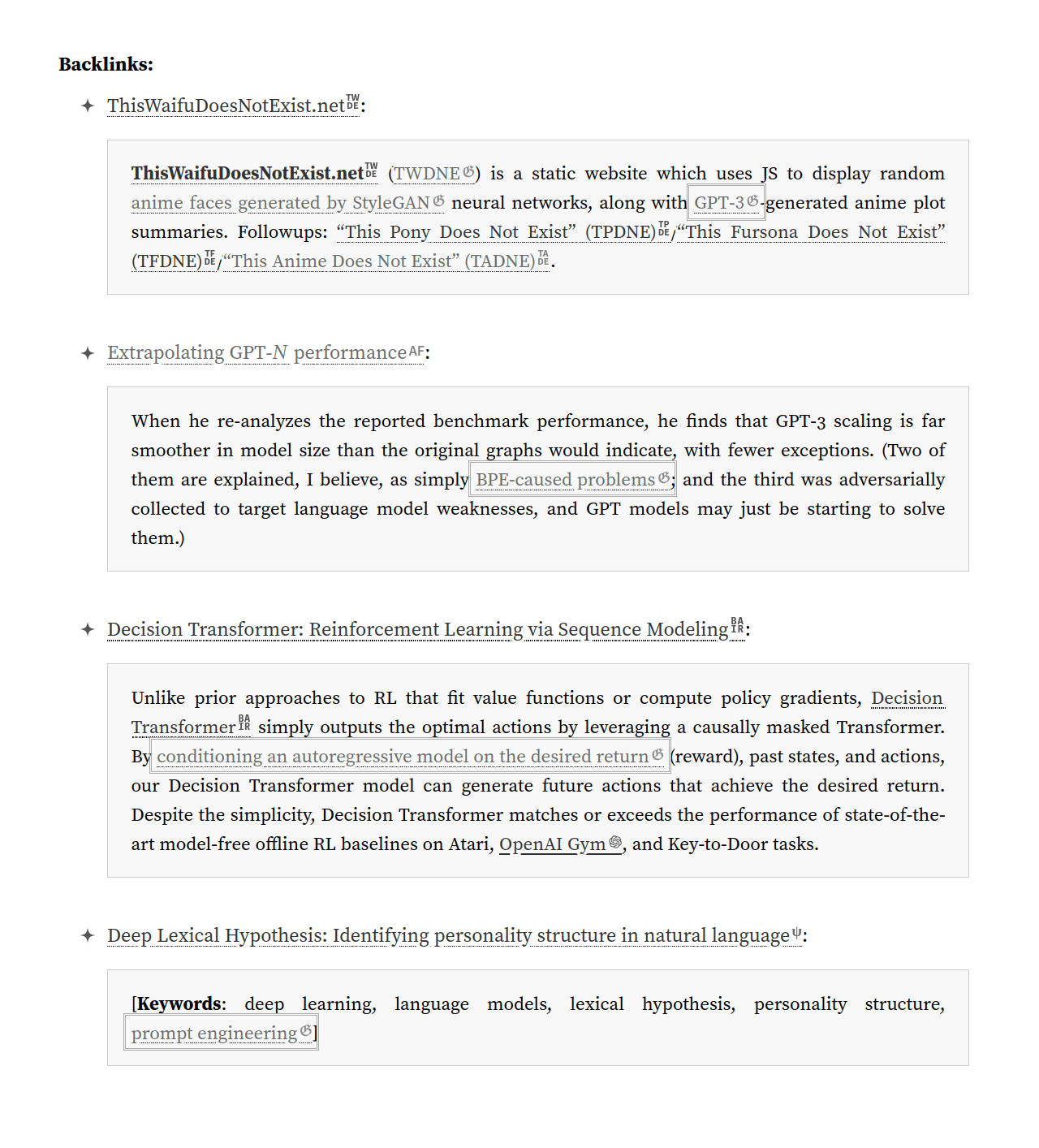

Another unique feature of Gwern.net backlinks is that they integrate with the annotation popups. Most wikis are able to provide backlinks only for wiki pages linking to each other; they cannot provide either backlinks or forward-links between arbitrary URLs and wiki pages. Gwern.net backlinks, however, can be from any URL to any URL: page ↔︎ page, page ↔︎ URL, and URL ↔︎ URL (although if there is no annotation to display that metadata, the reader has no way to see this). This is done by simply including the annotations in the files parsed for links, and attributing a link in the annotation to its respective URL, and proceeding as usual. So for example, I have linked my GPT-3 page in many annotations about deep learning because it describes concepts I consider key to interpreting deep learning results such as “prompt engineering”, and those show up in its backlinks even though they are not ‘Gwern.net pages’ or ‘wiki articles’:

The GPT-3 page’s backlinks, showing backlinks from research articles which have annotations linking to it, and not just top-level pages (another example).

But, annotations can also link to each other, creating an implicit citation graph (smaller than the ones created by analysis of papers & bibliographies like Google Scholar, but thereby more targeted to my uses):

An example of a research paper linked in the annotation of another paper, as displayed in its annotation popup (cropped for size).

This solves the problem of spam backlinks, which killed the old blogosphere’s use of linkbacks. If someone at an external URL links to a Gwern.net URL (or any URL) and I want to include that in the citation graph, I can simply create an annotation for their external URL and include their targeted link. Now that will automatically show up in the backlinks.

Implementation

The existence of HTML identifying IDs on the <a> hyperlink elements is critical to making bidirectional links work: one cannot link what one cannot name.9 Because URLs can be linked multiple times for different uses in a page10, the URL is not enough; knowing that a URL is linked inside a page is ambiguous, and one needs the URL plus an ID—only the pair is unique. This is where most backlink approaches fall short, and are forced to settle for the MediaWiki-style dump of backlinks with no possible context.

Hyperlinks (or targets like <span> elements) are assigned unique IDs manually, by Pandoc automatically, or using the annotation metadata to generate a predictable ID.11 (HTML IDs cannot start with a number or contain a period, among other restrictions, so the generated IDs typically take the form of #surname-year; thus, a link to the GPT-3 paper et al 2020 will have the ID in this page of #brown-et-al-2020 and that link in this paragraph can be addressed as /design#brown-et-al-2020. Duplicate IDs are fixed by either a global override to disambiguate two links, or per-page manually-assigned IDs.)

Backlinks are implemented as an offline process which parses the Markdown sources for pages & the HTML for annotations, and extracts URLs+IDs. They could be implemented at compile-time, but it is not a good fit for a static site generator like Hakyll, so I simply run the backlinks as a cron job at night. Backlinks are not always of any interest (eg. links in newsletters are usually devoid of any interesting commentary or context), and can be disabled on a per-link basis with a .backlink-not attribute.

They are then turned into appropriately-formatted HTML lists of transclusions, one snippet per URL. These are then transcluded again in collapsed sections for that URL, however that is displayed.12

Because the backlinks exploit the general transclusion & collapse functionality, their frontend integration is mostly a matter of just updating the generated HTML snippets and the occasional template. One might ask how one handles a URL+ID when the URL is not a simple HTML page on Gwern.net, but is perhaps a PDF or a URL on another site (and the URL may not even exist due to linkrot)? The answer is simple: it is just rewritten to to the URL of the annotation HTML snippet + ID, and transcluded. (It’s transclusions all the way down!)

The main challenge comes from a few edge-cases where the backlink popups wouldn’t work seamlessly. For backlinks from an external URL’s annotation, the pop-up JavaScript must guess the URL inside the annotation to provide context. Additionally, a data-target-id attribute must be stored inside backlinks to distinguish IDs from actual anchors. (We considered simply concatenating them like #target#id, but that in-band encoding simply led to different ambiguities.)

Other Uses

The backlink database has a few other uses:

A backlink database is a forward-link database if one inverts the query or schema. So if one wants a list of links in a page (ie. its forward-links), one can skip parsing the file and just query the backlink database.

This enables site-wide analyses of links; one use is combining it with the link-icon & site-of-the-day features to list domains which are used frequently enough to justify a link-icon or inclusion in site-of-the-day, and to look for frequently-linked but unannotated links.

The backlinks are also used to generate neural net embeddings for annotations (currently used only for the ‘similar links’ recommendations—is this the Semantic Web‽—but I intend to use for other purposes like tag refactoring), enriching their metadata with their site-wide context.

Similar Links

Gwern.net provides similar links (eg. this page) where possible, which are a list of annotations which are semantically ‘similar’ to the current one. ‘Similar’ is currently defined as an ordinary k nearest-neighbors lookup on a neural net embedding of the annotation text.

Uniquely, similar-links are also “sorted” by embedding distance, which organizes the list of similar links in a logical fashion & makes it more readable.

Link Bibliographies

Gwern.net pages & annotations provide a link bibliography (eg. this page): a list of their hyperlinks in order, with the annotation automatically expanding.

Because of the annotations, we do not provide the usual ‘Reference’ or ‘Bibliography’ section, but rather something closer to an ‘annotated bibliography’. This lets one skim the ‘annotated bibliography’ of a page, rather than having to pop up links one by one.

Abandoned

Tools

Software tools & libraries used in the site as a whole:

The source files are written in Pandoc Markdown (Pandoc: John MacFarlane et al; GPL) (source files: Gwern Branwen, CC-0). The Pandoc Markdown uses a number of extensions; pipe tables are preferred for anything but the simplest tables; and I use semantic linefeeds (also called “semantic line breaks” or “ventilated prose”) formatting.

math is written in LaTeX which compiles to MathML, rendered statically by MathJax (Apache license) into HTML/CSS/fonts; copy-paste of the original math expression is handled by a JavaScript copy-paste listener

syntax highlighting: we originally used Pandoc’s builtin Kate-derived themes, but most clashed with the overall appearance; after looking through all the existing themes, we took inspiration from Pygments’s algol_nu (BSD) based on the original ALGOL report, and typeset it in the IBM Plex Mono font26

the site is compiled with the Hakyllv4+ static site generator, used to generate Gwern.net, written in Haskell (Jasper Van der Jeugt et al; BSD); for the gory details, see

hakyll.hswhich implements the compilation, RSS feed generation, & parsing of interwiki links as well. This just generates the basic website; I do many additional optimizations/tests before & after uploading, which is handled bysync.sh(Gwern Branwen, CC-0)My preferred method of use is to browse & edit locally using Emacs, and then distribute using Hakyll. The simplest way to use Hakyll is that you

cdinto your repository andrunghc hakyll.hs build(withhakyll.hshaving whatever options you like). Hakyll will build a static HTML/CSS hierarchy inside_site/; you can then do something likefirefox _static/index. (Because HTML extensions are not specified in the interest of cool URIs, you cannot use the Hakyllwatchwebserver as of January 201412ya.) Hakyll’s main advantage for me is relatively straightforward integration with the Pandoc Markdown libraries; Hakyll is not that easy to use, and so I do not recommend use of Hakyll as a general static site generator unless one is already adept with Haskell.the CSS is borrowed from a motley of sources and has been heavily modified, but its origin was the Hakyll homepage & Gitit; for specifics, see

default.cssMarkdown syntax extensions:

I implemented a Pandoc Markdown plugin for a custom syntax for interwiki links in Gitit, and then ported it to Hakyll (defined in

hakyll.hs); it allows linking to the English Wikipedia (among others) with syntax like[malefits](!Wiktionary)or[antonym of 'benefits'](!Wiktionary "Malefits"). CC-0.inflation adjustment:

Inflation.hsprovides a Pandoc Markdown plugin which allows automatic inflation adjusting of dollar amounts, presenting the nominal amount & a current real amount, with a syntax like[$5]($1980).Book affiliate links are through an Amazon Affiliates tag appended in the

hakyll.hsimage dimensions are looked up at compilation time & inserted into

<img>tags as browser hints

JavaScript:

the HTML tables are sortable via tablesorter (Christian Bach; MIT/GPL)

the MathML is rendered using MathJax

analytics are handled by Google Analytics

A/B testing is done using ABalytics (Daniele Mazzini; MIT) which hooks into Google Analytics (see testing notes) for individual-level testing; when doing site-level long-term testing like in the advertising A/B tests, I simply write the JavaScript manually.

Generalized tooltip popups for loading introductions/summaries/previews of all links when one mouses-over a link; reads annotations, which are manually written & automatically populated from many sources (Wikipedia, Pubmed, BioRxiv, Arxiv, hand-written…), with special handling of YouTube videos (Said Achmiz, Shawn Presser; MIT).

Note that ‘links’ here is interpreted broadly: almost everything can be ‘popped up’. This includes links to sections (or div IDs) on the current or other pages, PDFs (often page-linked using the obscure but handy

#page=Nfeature), source code files (which are syntax-highlighted by Pandoc), locally-mirrored web pages, footnotes/sidenotes, any such links within the popups themselves recursively…the floating footnotes are handled by the generalized tooltip popups (they were originally implemented via

footnotes.js); when the browser window is wide enough, the floating footnotes are instead replaced with marginal notes/sidenotes27 using a custom library,sidenotes.js(Said Achmiz, MIT)

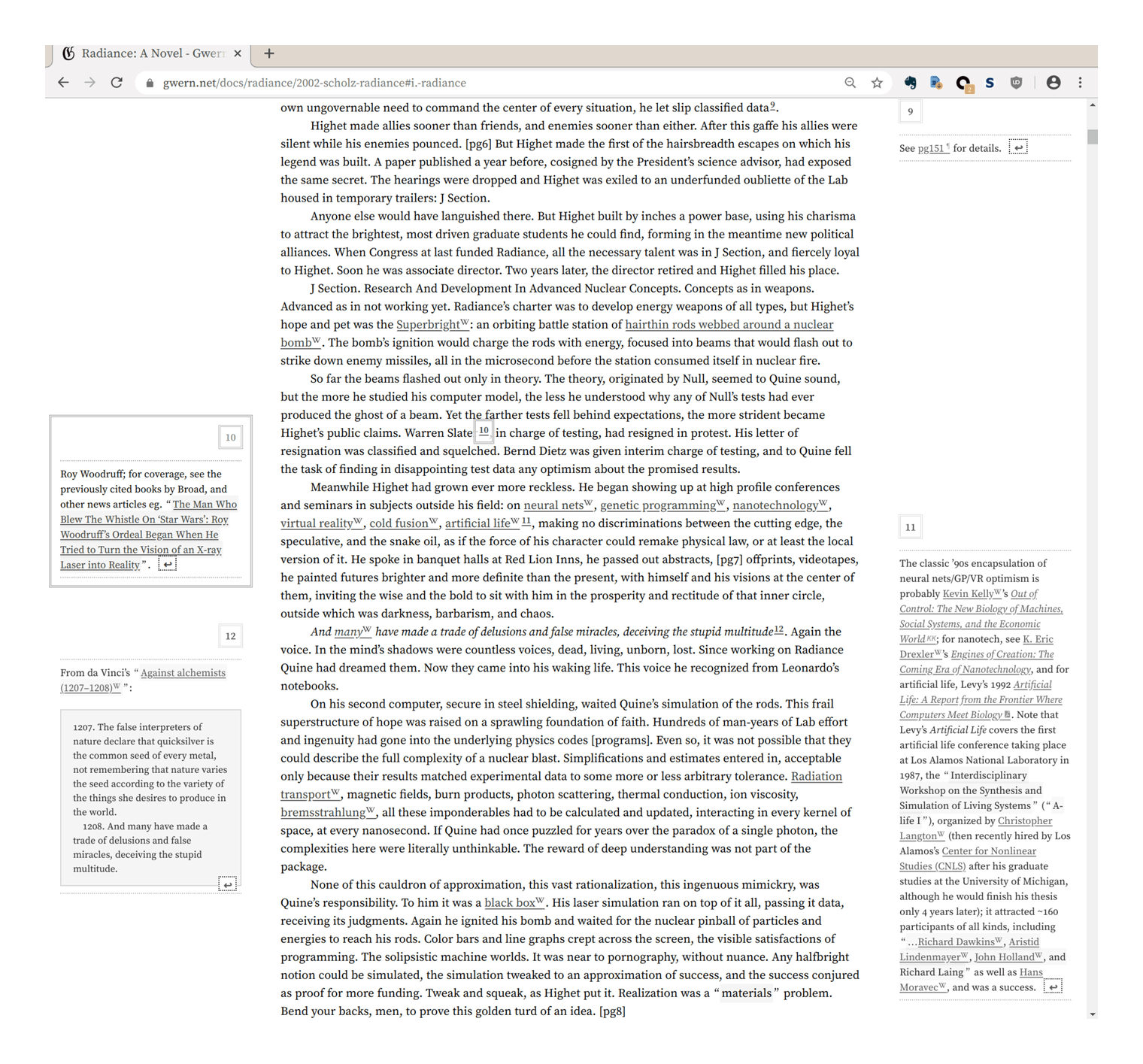

Demonstration of sidenotes on Radiance.

image size: full-scale images (figures) can be clicked on to zoom into them with slideshow mode—useful for figures or graphs which do not comfortably fit into the narrow body—using another custom library,

image-focus.js(Said Achmiz; GPL)

error checking: problems such as broken links are checked in 3 phases:

markdown-lint.sh: writing timesync.sh: during compilation, sanity-checks file size & count; greps for broken interwikis; runs HTML tidy over pages to warn about invalid HTML; tests liveness & MIME types of various pages post-upload; checks for duplicates, read-only, banned filetypes, too large or uncompressed images, etc.

Implementation Details

The Programmers’ Credo: “We do these things not because they are easy, but because we thought they were going to be easy.”

There are some tricks & details that web designers might find interesting.

Efficiency:

fonts:

Adobe Source Serif/Sans (originally Gwern.net used Baskerville)

Why use our own webfonts instead of just using pre-existing web-safe/system fonts? One might ask if the font overhead (non-blocking download of ~0.5MB of fonts for the most complex pages like the GPT-3 fiction page) is worth it, compared to trusting in fonts that may be installed already and are ‘free’ network-wise. This is what our webfonts buys us:

correctness (consistent rendering):

The fundamental reason for not using system fonts is that there are not many of them, they vary across operating systems & devices, usually aren’t great (lacking alternatives & features like smallcaps, & often basics like Unicode), and can be buggy (eg. Apple ships a Gill Sans digitization—not an obscure font!—which is >22 years old & has broken kerning).

I initially used system “Baskerville”, but they looked bad on some screens (similar issue to people imitating LaTeX by using Computer Modern on screens) and the highly limited selection of system fonts didn’t give me many options. The Google Fonts Baskerville was OK but lacked many features & was slower than hosting my own webfont, so Said Achmiz convinced me to just switch to self-hosting the ‘screen serif’ Source family, whose appearance I liked, which could be subset down to only necessary characters to be faster than Google Fonts & not a bottleneck, and which wasn’t widely used then despite being FLOSS & high-quality & actively maintained (so helped my personal branding).

We were then repeatedly forced to add more fonts to fix display bugs: fonts could look quite different on Linux & Mac, and the system “sans” for the Table of Contents looked bad on Windows. The more carefully designed the appearance, the more small differences in sizes or appearance between the ‘same’ font on different platforms screwed things up. Link-icons, sidenotes, emoji, return-arrows, miscellaneous Unicode looking rather different or breaking—all of these have run into platform issues, and later features like citation subscripts or inflation-adjustments surely would if we couldn’t tune their CSS to a known font.

(Should we let readers set their own fonts? Reader, be real. It is 2023, not 199333ya. No one today sets their own fonts or writes custom CSS stylesheets—which would break layout & icons on many sites anyway—and they especially do not on the mobile devices which are ~50% of my site traffic.)

smallcaps: used extensively in the site design for varying levels of emphasis in between bold & italics, so high quality smallcaps is critical; true smallcaps is provided by Source (italics may yet be added at my request), while unavailable in most fonts

consistent monochrome emoji via Noto Emoji (before, emoji would be different sizes in link-icons, some would be unpredictably colored on some platforms and scream on the page)

IBM Plex Mono for source code: more distinct confusable-characters in IBM Plex Mono compared to an ordinary monospace system font (Plex Mono has an OpenType feature for slashed-zeros which can be enabled in just source code), and looks good on Macs.28

the Source family also provides both tabular & proportional numbers (also called “old-style”), which most fonts don’t, and which makes tables vs text more readable (proportional numbers would break visual alignment inside tables analogous to proportional vs monospace fonts for code, while tabular numbers look large & obtrusive inside regular text)

icons via Quivira font, and rare characters like interrobang, asterism, backwards question mark, shield-with-cross (for link icon), BLACK SQUARE ■, and consistency in fallback characters for rare Unicode points not in the subsets.

efficient dropcaps fonts by subsetting

image optimization: PNGs are optimized by

pngnq/advpng, JPEGs withmozjpeg, SVGs are minified, PDFs are compressed withocrmypdf’s JBIG2 support. (GIFs are not used at all in favor of WebM/MP4<video>s.)JavaScript/CSS minification: because Cloudflare does Brotli compression, minification of JavaScript/CSS has little advantage29 and makes development harder, so no minification is done; the font files don’t need any special compression either beyond the subsetting.

MathJax: getting well-rendered mathematical equations requires MathJax or a similar heavyweight JavaScript library; worse, even after disabling features, the load & render time is extremely high—a page like the embryo selection page which is both large & has a lot of equations can visibly take >5s (as a progress bar that helpfully pops up informs the reader).

The solution here is to prerender MathJax locally after Hakyll compilation, using the local tool

mathjax-node-pageto load the final HTML files, parse the page to find all the math, compile the expressions, define the necessary CSS, and write the HTML back out. Pages still need to download the fonts but the overall speed goes from >5s to <0.5s, and JavaScript is not necessary at all.Automatic Link-Ification Regexps: I wrote

LinkAuto.hs, a Pandoc library for automatically turning user-defined regexp-matching strings into links, to automatically turn all the scientific jargon into Wikipedia or paper links. (There are too many to annotate by hand, especially as new terms are added to the list or abstracts are generated for popups.)“Test all strings against a list of regexps and rewrite if they match” may sound simple and easy, but the naive approach is exponential: n strings, r regexps tested on each, so 𝒪(nr) matches total. With >600 regexps initially & millions of words on Gwern.net… Regexp matching is fast, but it’s not that fast. Getting this into the range of ‘acceptable’ (~3× slowdown) required a few tricks.

The major trick is that each document is converted to a simple plain text format, and the regexps are run against the entire document; in the average case (think of short pages or popup annotations), there will be zero matches, and the document can be skipped entirely. Only the matching regexps get used in the full-strength AST traversal. While it is expensive to check a regexp against an entire document, it is an order of magnitude or two less expensive than checking that regexp against every string node inside that document!

Correctness:

Dark mode (): our dark mode is custom, and tries to make dark mode a first-class citizen.

Avoiding Flashing & Laggy Scrolling: it is implemented in the standard best-practice way of creating two color palettes (associating a set of color variables for every element, for a light-mode and then automatically-generating dark mode colors by inverting & gamma-correcting), and using JavaScript to toggle the media-query to instantly enable that color.

This avoids the ‘flash of white’ on page loads which regular JavaScript-based approaches incur (because the CSS media-queries can only implement auto-dark-mode, and the dark mode widget requires JavaScript; however, the JavaScript, when it decides to inject dark mode CSS into the page, is too late and that CSS will be rendered last after the reader has already been exposed to the flash). The separate color palette approach also avoids the lag & jank of using invert CSS filters (one would think that

invert(100%)would be free from a performance standpoint, since what pixel manipulation could be simpler than negating the color?—but it is not).Native Dark Mode Color Scheme: we modify the color scheme as necessary.

Because of the changes in contrast, inverting the color scheme only mostly works. In particular, inline & code blocks tend to disappear. To fix this, we allow a small deviation from pure-monochrome to add some blue, and the source code syntax highlighting is tweaked with a few blue/purple/red colors for dark mode visibility (since there’s not any logical dark-mode equivalent of the ALGOL syntax-highlighting style).

Inverted Images: color images are desaturated & grayscaled by default to reduce their brightness; grayscale/monochrome images, are automatically inverted by a machine-learning API, InvertOrNot.com.

This avoids the common failure mode where a blog uses a dark mode library which implements the class approach correctly… but then all of their images still have blinding bright white backgrounds or overall coloration, defeating the point! However, one also cannot just blindly invert images because many images, photographs of people especially, are garbage as ‘photo-negatives’.

Default Your Devices To Dark Mode

If you add a dark mode to your app or website, set your devices to dark mode on it—even if you don’t like dark mode or it’s inappropriate.

You will have dark mode-only bugs, but your readers will never tell you about the bugs, particularly the odd one-off bugs. You will see your light-mode often enough due to logged-out devices or screenshots or regular development, so you need to force yourself to use dark mode.

Three-Way Dark Mode Toggle: Many dark modes are implemented with a simple binary on/off logic stored in a cookie, ignoring browser/OS preferences, or simply defining ‘dark mode’ as the negation of the current browser/OS preference.

This is incorrect, and leads to odd situations like a website enabling dark mode during the day, and then light mode during the night! Using an auto/dark/light tri-state toggle means that readers can force dark/light mode but also leave it on ‘auto’ to follow the browser/OS preference over the course of the day.

This requires a UI widget & it still incurs some of the problems of an auto-only dark mode, but overall strikes the best balance between enabling dark mode unasked, reader control/confusion, and avoiding dark mode at the wrong time.

collapsible sections: managing complexity of pages is a balancing act. It is good to provide all necessary code to reproduce results, but does the reader really want to look at a big block of code? Sometimes they always would, sometimes only a few readers interested in the gory details will want to read the code. Similarly, a section might go into detail on a tangential topic or provide additional justification, which most readers don’t want to plow through to continue with the main theme. Should the code or section be deleted? No. But relegating it to an appendix, or another page entirely is not satisfactory either—for code blocks particularly, one loses the literate programming aspect if code blocks are being shuffled around out of order.

A nice solution is to simply use a little JavaScript to implement code folding approach where sections or code blocks can be visually shrunk or collapsed, and expanded on demand by a mouse click. Collapsed sections are specified by a HTML class (eg.

<div class="collapse"></div>), and summaries of a collapsed section can be displayed, defined by another class (<div class="abstract-collapse">). This allows code blocks to be collapse by default where they are lengthy or distracting, and for entire regions to be collapsed & summarized, without resorting to many appendices or forcing the reader to an entirely separate page.Sidenotes: one might wonder why

sidenotes.jsis necessary when most sidenote uses are like Tufte-CSS and use a static HTML/CSS approach, which would avoid a JavaScript library entirely and visibly repainting the page after load?The problem is that Tufte-CSS-style sidenotes do not reflow and are solely on the right margin (wasting the considerable whitespace on the left), and depending on the implementation, may overlap, be pushed far down the page away from their, break when the browser window is too narrow or not work on smartphones/tablets at all. (This is fixable, Tufte-CSS’s maintainers just haven’t.) The JavaScript library is able to handle all these and can handle the most difficult cases like my annotated edition of Radiance. (Tufte-CSS-style epigraphs, however, pose no such problems and we take the same approach of defining an HTML class & styling with CSS.)

Link icons: icons are defined for all filetypes used in Gwern.net and most commonly-linked websites such as Wikipedia, or Gwern.net (within-page section links get up/down-arrows to indicate relative position, with ‘¶’ as a JavaScript-less fallback; cross-page links get the logo icon).

They are implemented in a scalable compile-time approach when the standard approach failed.

Redirects: static sites have trouble with redirects, as they are just static files. AWS 3S does not support a

.htaccess-like mechanism for rewriting URLs. To allowing moving pages & fix broken links, I wroteHakyll.Web.Redirectfor generating simple HTML pages with redirect metadata+JavaScript, which simply redirect from URL 1 to URL 2. After moving to Nginx hosting, I converted all the redirects to regular Nginx rewrite rules.In addition to page renames, I monitor 404 hits in Google Analytics to fix errors where possible, and Nginx logs. There are an astonishing number of ways to misspell Gwern.net URLs, it turns out, and I have defined >20k redirects so far (in addition to generic regexp rewrites to fix patterns of errors).

External Links

Discussion: HN

“Experience True Level” (Rick and Morty, S3E8 “Morty’s Mind Blowers”)

Appendix

Returns To Design?

What is the ‘shape’ of returns on investment in industrial design, UI/UX, typography etc.? Is it a sigmoid with a golden mean of effort vs return… or a parabola with an unhappy valley of mediocrity?

My experience with Gwern.net design improvements is that readers appreciated changes moderately early on in making its content more pleasant to read (if only by comparison to the rest of the Internet!), but after a certain point, it all ‘came together’, in some sense, and readers started raving over the design and pointing to Gwern.net’s design rather than its content. This is inconsistent with the default, intuitive model of ‘diminishing returns’, where each successive design tweak should be worth less than the previous one.

Is there a ‘perfection premium’ (perhaps as a signal of underlying unobservable quality, or perhaps reader interaction is like an O-ring process)?

Impute—the process by which an impression of a product, company or person is formed by mentally transferring the characteristics of the communicating media…People do judge a book by its cover…The general impression of Apple Computer Inc. (our image) is the combined result of everything the customer sees, hears or feels from Apple, not necessarily what Apple actually is! We may have the best product, the highest quality, the most useful software etc.; if we present them in a slipshod manner, they will be perceived as slipshod; if we present them in a creative, professional manner, we will impute the desired qualities.

Mike Markkula, “The Apple Marketing Philosophy: Empathy • Focus • Impute” (1977-12)

Si paulum summo decessit, vergit ad imum

Particularly with typography, there seems to be an infinite number of finicky details one could spend time on (much of which appears to be for novelty’s sake, while vastly more important things like advertising harms go ignored by so-called designers). One’s initial guess is that it’d be diminishing returns like most things: it’d look something like a log curve, where every additional tweak costs more effort as one approaches the Platonic ideal. A more sophisticated guess would be that it’d look like a sigmoid: at first, something is so awful that any fixes are irrelevant to the reader because that just means they suffer from a different problem (it doesn’t matter much if a website doesn’t render because of a JavaScript bug if the text when it does render is so light-shaded that one can’t read it); then each improvements makes a difference to some readers as it approaches a respectable mediocrity; and after that, it’s back to diminishing returns.

My experience with improving the design of Gwern.net & reading about design has made me wonder if either of those is right. The shape may resemble more of a parabola: the sigmoid, at some point, spikes up and returns increase rather than diminish?

I noticed that for the first half-decade or so, no one paid much attention to the tweaks I made, as it was an ordinary Markdown-based static site. As I kept tinkering, a comment would be made once in a while. When Said Achmiz lent his talents to adding features & enhancements and exploring novel tweaks, comments cropped up more frequently (consistent with the enormous increase in time spent on it); by 2019, the redesign had mostly stabilized and most of the signature features & visual design had been implemented, and 2020 was more about bug fixes than adding pizzazz. Under the intuitive theories, the rate of comments would be about the same: while the bug fixes may involve huge effort—the dark mode rewrite was a 3-month agony—the improvements are ever smaller—said rewrite had no reader-visible change other than removing slowness. But while site traffic remained steady, 2020 attracted more compliments than ever!

Similarly, the LW team put an unusual amount of effort into designing a 2018 essay compilation, making it stylish (even redrawing all the images to match the color themes), and they were surprised by unusually large the preorders were: not a few percentage points, but many times. (There are many books on data visualization, but I suspect Edward Tufte’s books outsell them, even the best, by similar magnitudes.) And what should we make of Apple & design, whose devices & software have glaring flaws and yet, by making more of an attempt, command a premium and are regarded well by the public? Or Stripe?30

If the sigmoid were right, just how much more effort would be necessary to elicit such jumps? Orders of magnitude more? I & Said have invested effort, certainly, but there are countless sites (even confining the comparison to just personal websites and excluding sites with professional full-time developers/designers), whose creators have surely invested more time; millions of books are self-published every year; and Apple is certainly not the only tech company which tries to design things well.

What might be going on is related to the “aesthetic-usability effect”: at a certain level, the design itself becomes noticeable to the reader for its esthetic effect and the esthetics itself becomes a feature adding to the experience. That is, at the bottom of the sigmoid, on a website strewn with typos and broken links and confusing colors, the reader thinks “this website sucks!”, while in the middle, the reader ceases to think of the website at all and just gets on with using it, only occasionally irritated by design flaws; finally, at a certain level, when all the flaws have been removed and the site itself is genuinely unironically beautiful, both the beauty & absence of flaws themselves become noticeable, and the reader thinks, “this website, it is—pretty awesome!” The spike is where suddenly the design itself is perceived as a distinct thing, not merely how the thing happens to be. Designers often aspire to an end-state of sprezzatura or the “crystal goblet”, where they do their job so well the reader doesn’t realize there was a job to be done at all—but in this fallen world, where excellence seems so rare, the better one does the job, the more the contrast with all the botched jobs inevitably draws attention.

It is difficult for even the reader least interested in the topic to open a Tufte book, or walk into an Apple store, and not be struck by first impressions of elegance and careful design—which is not necessarily a good thing if that cannot be lived up to. (Any person struck by this must also realize that other people will be similarly impressed, using their own response as a proxy for the general reaction31, and will take it as a model for aspiration; liking Apple or Tufte signals your good taste, and that makes them luxury products as much as anything.)

The reason it makes an impression might be that it serves as a costly signal that if you care enough to visibly “get it right”, even where that requires unreasonable effort, then you probably can be trusted to get it right on things where other people can’t easily see that. Since it’s so hard to judge software quality without extensive use (and is borderline impossible for things like security & privacy), as opposed to furniture32, people especially rely on these sorts of heuristics.

This suggests a dangerous idea (dangerous because a good excuse for complacency & mediocrity, especially for those who do not manage even mediocrity but believe otherwise): if you are going to invest in design, half-measures yield less than half-results. If the design is terrible, then one should continue; but if the design is already reasonable, then instead of there being substantial returns, the diminishing returns have already set in, and it may be a too-long slog from where you are to the point where people are impressed enough by the design for the esthetic effect to kick in. Those moderate improvements may not be worthwhile if one can only modestly improve on mediocrity; and a sufficiently-flawed design may not be able to reach the esthetic level at all, requiring a radical new design.