Excerpts from Little Boy

Short essays on the influence on Japanese culture of anime works Daicon, Evangelion, Space Battleship Yamato, and the artists Mr., Chiho Aoshima, and others.

This transcript has been prepared from a PDF scan of pages 9–10, 40, 52–53, 70, & 88 of Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture, edited by Takashi Murakami, published 2005-05-15, ISBN 0300102852.

These pages are drawn from the first section of Little Boy, “Little Boy (Plates and Entries)”, a sort of collection of encyclopedic entries on various anime, artists, and artworks. I have selected a few entries that were striking or of personal interest.

Neon Genesis Evangelion

[pg88]

Neon Genesis Evangelion, an anime masterpiece, began as a TV series written and directed by Hideaki Anno and produced by Gainax in 1995–96. The production company Gainax got its start as DAICON Film, a group of amateur animators who created DAICON IV Opening Animation [videos] (pl. 2) in 198343ya, and its affiliate, the science-fiction store General Products; essentially a group of otaku elites, they were professional incorporated as Gainax in 198442ya upon production of the feature-length anime The Wings of Honneamise (released in 198739ya). Evangelion became an explosive hit when it was first broadcast. Caught up in the cult-like fervor surrounding the work, fans willingly accepted the controversial and irregular release of the subsequent film: unable to complete it on time, Gainax showed an unfinished version to paying audiences in March 199729ya and released the final version a few months later. The original TV series and the subsequent feature films attracted not only anime fans but also young culture-lovers and anime veterans who had outgrown otaku obsessions. Evangelion is an unsurpassed milestone in the history of otaku culture.

The story is set in 201511ya, fifteen years after the Second Impact, a deadly cataclysm of global magnitude that originated in Antarctica. The new city of Tokyo 3 is suddenly attacked by “Angels”, unidentified enemies that take various forms including biomechanical giants and a computer virus. NERV, a special U.N. agency charged with fighting the invaders, deploys Evangelions, all-purpose humanoid weapons piloted by three specially chosen fourteen-year-old kids (Shinji, Rei, and Asuka). A complex amalgam of science fiction and human drama in the form of robot anime, Evangelion showcased Gainax’s skillful animation, along with Anno’s bold use of white-on-black subtitle graphics and speedy, almost subliminal construction of action sequences. In many ways, Evangelion is a meta-otaku film, through which Anno, himself an otaku, strived to transcend the otaku tradition. This superbly crafted work was infused with intriguing, often cryptic terms and ideas adapted liberally from sources as disparate as Judeo-Christian mysticism, biology, and psychology. Such elements include the devastating weapon “Spear of Longinus” (derived from the legendary spear used to pierce the crucified Jesus) and the “AT (Absolute Terror) Field” (essentially, a mental barrier separating a person’s ego from the outside world).

While dutifully paying homage to the pop- and otaku-culture landmarks that preceded it, Evangelion pushed its depiction of the psychological and emotional struggles of the young motherless pilots to the extreme. The controversial final two episodes of the TV series, which unconventionally mix anime scenes with drawings and video footage, focus on Shinji, the central character among the pilots, and his painful search for what his life means both as a person and as an Evangelion pilot. With the purposeless Shinji’s interior drama taking center stage, Evangelion is the endpoint of the postwar lineage of otaku favorites—from Godzilla to the Ultra series to Yamato to Gundam (pls. 7, 9, 27, 30)—in which hero-figures increasingly question and agonize over their righteous missions to defend the earth and humanity. Shinji’s identity crisis, apparently a reflection of the director Anno’s own psychological dilemmas, epitomized the difficult obstacles faced by postwar Japan, a nation that had recovered from the trauma of war only to find itself incapable of creating its own future: like Shinji, Japan is probing the root cause of its existential paralysis.

[Plates 33a-j; Neon Genesis Evangelion; 1995–96; 26-episode TV anime series; Director: Hideaki Anno; Animation production: Gainax and Tatsunoko Productions; Created by Gainax; Broadcast by TV Tokyo; Additional images taken from Neon Genesis Evangelion: Death and Rebirth (199729ya); Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion (199729ya); Revival of Evangelion (199828ya); and VHS/DVD edition of Neon Genesis Evangelion (199828ya)]

[Plate 33a; Rei Ayanami]

[Plate 33b; Lilith penetrated by “Spear of Longinus”]

[Plate 33c; Scenes from Evangelion]

[Plate 33d; A motherly figure]

[Plate 33e; Clones of Rei Ayanami]

[Plate 33f; Gendo Ikari, Shinji’s father and NERV Commander]

[Plate 33g; Shinji Ikari as a young boy]

[Plates 33h-j; From “One More Final” scene of The End of Evangelion; 199729ya]

Daicon IV Opening Animation

[pg9–10]

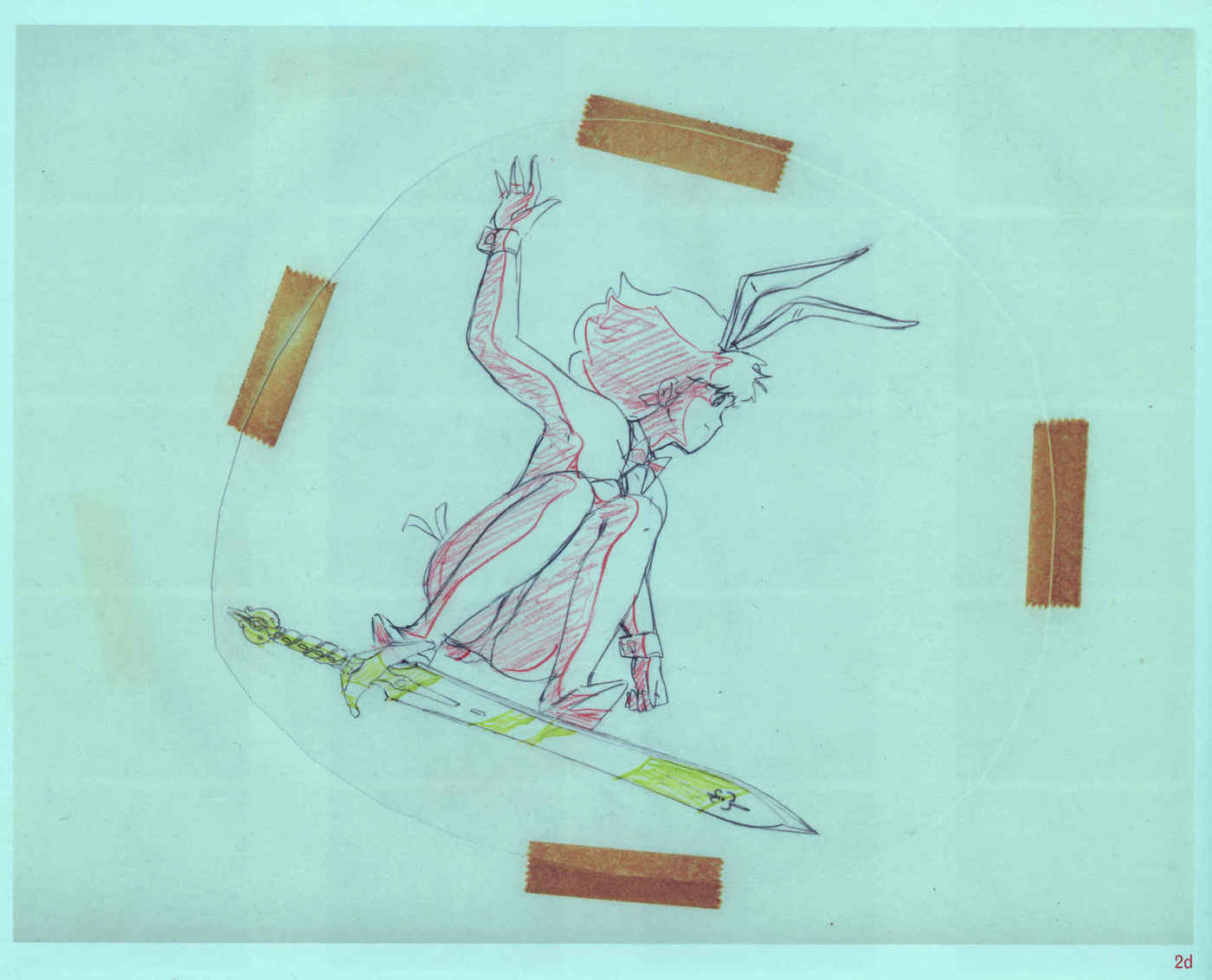

A cel of the ‘bunny girl’ in DAICON IV —Editor

Storyboard (?) of the swords engaged in an “Itano circus” in DAICON IV —Editor

DAICON IV Opening Animation was first shown at the opening ceremony of the 22nd Japan SF Convention held in Osaka in 198343ya. Created by DAICON Film, a group of amateur animators, this five-minute 8mm film was a sequel to the group’s debut work, DAICON III Opening Animation, which premiered at the 198145ya conference (also in Osaka). DAICON stands for “Osaka Convention”, using an alternate pronunciation (dai) for the first character in “Osaka”.

The annual SF (science fiction) convention, inaugurated in 196264ya, remains an event by otaku for otaku, predating the term otaku itself, which did not enter public discourse until the late 1980s. Science fiction is intimately linked to otaku culture. The creators of such otaku-favored genres as “robot anime” and tokusatsu (special effects) films drew heavily on science fiction; the anime classic Mobile Suit Gundam (pl. 30), for example, was inspired by Robert 1959 novel, Starship Troopers. Before the full emergence of otaku culture, fans of tokusatsu and anime TV series created for children could further satisfy their appetites only by turning to science fiction.

DAICON Film was formed by Toshio Okada, Yasuhiro Takeda, Hideaki Anno, Hiroyuki Yamaga, and Takami Akai (among others), who were then college students in the Osaka area. They subsequently formed the anime studio Gainax, which made its name with Neon Genesis Evangelion (pl. 33) in 199531ya, a landmark of otaku culture.

Their DAICON animations reveal two characteristics that appeal to otaku. First, they would contain abundant references to elements of the subculture that would later be called otaku subculture, including Godzilla and Space Battleship Yamato (pls. 7, 27). Second, even though these hand-drawn, 8mm anime films are extremely short at five minutes each, they demonstrate an extraordinary artistic and technical level that exceeds expectations for independent films: not only is the quality of the animation high, but the DAICON animators were able to integrate the picture and the music seamlessly and deploy such sophisticated techniques as multiple exposures far more skillfully than “professionals”. Indeed, DAICON’s films, imbued with a tremendous amount of energy and the ambition of these amateur animators, jump-started the evolution of anime subculture into full-fledged otaku culture.

In the final sequence of DAICON IV Opening Animation, the theme of “destruction and regeneration” is imaginatively reinterpreted. The energetic flight through the sky of a girl in a bunny costume is followed by the explosion of what could only be described as an atomic bomb, which destroys everything. In a pink-hued blast, petals of cherry blossoms—Japan’s national flower—spread over the city, which is then burned to ashes, as trees die on the mountains and the earth is turned into a barren landscape. When the spaceship DAICON, a symbol for otaku floating in the sky, launches a powerful “otaku” beam, the earth is covered with green, as giant trees sprout instantly from the ground. The world is revived, becoming a place of life where people joyously gather together.

Finding something liberating in the devastating power of destruction, the DAICON animators announced their revolution in pictorial form, paying little heed to the conventions of political correctness that surround the atomic bombings in Japan.

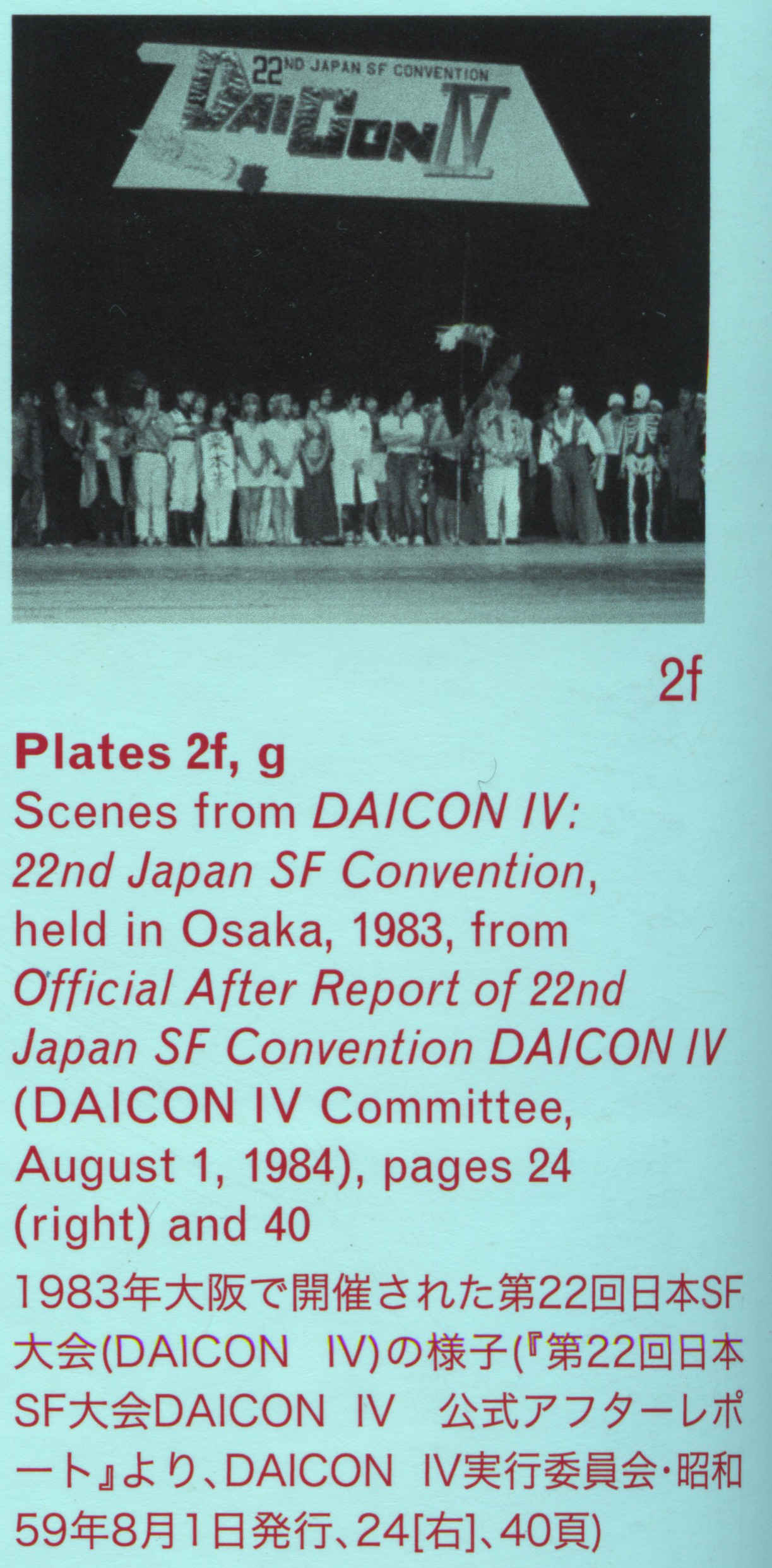

[Plate 2f-g; Scenes from DAICON IV: 22nd Japan SF Convention, held in Osaka, 198343ya, from Official After Report of 22nd Japan SF Convention DAICON IV (DAICON IV Committee, August 1, 198442ya), pages 24 (right) and 40]

Plate 2f; Cosmic Entertainers Fair, a costume pageant that gathered “the best in the universe”

Plate 2g; Toshio Okada addressing four hundred attendees at a dinner party

Space Battleship Yamato

[pg70]

Space Battleship Yamato originated as a TV anime series broadcast in Japan in 1974–75; it also aired in the U.S. as Star Blazers in 197056ya.

The story is set in the year 2199, when Earth is attacked by Gamilus, an evil stellar empire. Nuclear pollution caused by the Gamilon bombing threatens to kill all remaining humans within a year. The desperate earthlings receive a message from the friendly planet Iscandar, 148 thousand light years away: to save themselves, they must retrieve Iscandar’s radiation neutralizer, “Cosmo Cleaner”. Using the blueprint sent with the message, the embattled humans build a “Wave Motion Engine” capable of traveling beyond the speed of light, and install it on the sunken Japanese battleship Yamato—Japan’s last hope in World War ii—which they salvage from the dried seabed and refit for the mission to save their planet.

Above all, Yamato was instrumental in the rise of the new subculture of otaku. The series initially suffered low ratings, in part because its theme and setting were too complex for its intended audience of elementary-school children, and also because it was broadcast opposite Heidi, an immensely popular anime series. When the series was rerun, however, Yamato began to draw attention, prompting independent screenings. With the blockbuster success of the film version, released in 197749ya, Yamato marked a milestone in the history of animation, spawning sequels both on TV and on film. The young people who supported Yamato were the original otaku, or “adults unable to grow up”.

Yamato also caused a paradigm shift in animation. Departing from the usual plot of “good vanquishes evil” so common in children’s programming, it acknowledged the enemy’s necessity in attacking Earth: the Gamilons must relocate, as their home planet is doomed to die. The highly realistic design of “mecha” (meka)—mechanical vessels and weapons—also set the standard for the genre of “mecha-robot anime”. Without Yamato there would have been no Gundam or Evangelion (pls. 30, 33).

Also significant was the influence Yamato exerted on Aum Shinrikyo (Aum Supreme Truth), a notorious religious cult that carried out arguably the worst terrorist attack in postwar Japanese history by dispersing deadly Sarin gas on the Tokyo subways in 199531ya. Aum produced a Yamato-like anime film for their proselytization efforts, and named their own air purifiers (which supposedly protected them from enemy attacks with poisonous gases and biological weapons) “Cosmo Cleaners”. This fact alone demonstrates the profound impact made by Yamato on Japanese culture.

Notably, this landmark anime still relied on the idea of radiation as a key narrative device. Thirty years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Japanese experience of the atomic bombings was beginning to fade into the past, but the memory could not be forgotten.

[Plates 27a-c; Space Battleship Yamato; 1974–75 (first series); 26-episode TV anime series; Original concept and planning: Yoshinobu Nishizaki; Director: Leiji (Reiji) Matsumoto; Broadcast by Yomiuri TV Network]

[Plate 27a; Battleship Yamato on the exposed ocean floor]

[Plate 27b; Yamato departing from Earth for Iscandar]

[Plate 27c; The ship’s powerful weapon, “Wave Motion Gun”]

Chiho Aoshima

[pg52–53]

Chiho Aoshima (b. 197452ya) loved to draw from childhood. She would secretly fill notebooks with explicit images, each of which she destroyed after completion. when one of her notebooks was discovered by her parents, she was scolded and stopped drawing.

Aoshima never went to art school, but during her senior year majoring in economics at Hosei University in Tokyo, she discovered computer graphs while working at a part-time job. In a sense, she began her career in art by watching others work on computers. The merit of computer design lies in its flexibility. It is easy to modify a composition or colors and duplicate small components. Even an amateur can constantly review her work on the monitor, be critiqued by her friends, and incorporate various changes afterwards. Computer-generated works have as many possibilities for output as the technologies available, which multiply with time. Aoshima’s works are frequently rendered in mural-size printouts more than thirty meters across; they can also be produced as chromogenic prints, a type of color print frequently used for photographs.

Aoshima’s work is a cross between popular manga and traditional scroll paintings. She freely alters the sizes and colors of her characters, and repeatedly uses the same data for such background elements as trees. She does not flaunt complex techniques or aim for spectacle, but focuses solely on fixing the messages she wants to convey on the monitor as quickly as possible. Very few men appear in Aoshima’s fantastic worlds, which are populated by female characters who are transformed into mountains and rivers, or disguised as fairies or living creatures (especially insects, snakes, and reptiles) in the natural world.

Aoshima has discovered an unprecedented freedom of image production in a complete digital world. In her recent collaboration with fashion designer Issey Miyake, models wore dresses printed with Aoshima’s images in Miyake’s runway show. Inspired by this sight, Aoshima became interested in the human figure and began creating figurative sculptures and mannequins.

[Plate 19; Chiho Aoshima; Magma Spirit Explodes, Tsunami is Dreadful (detail); 200422ya; Chromogenic print; 87.2

Magma Spirit Explodes, Tsunami is Dreadful, left half

Magma Spirit Explodes, Tsunami is Dreadful, right half

Mr.

[pg40]

Mr. (b. 196957ya) is something of an otaku. A genuine “lolicom” [sic] (Japanese shorthand for “Lolita complex”, and those possessing it), he is also a trash collector and an ex-biker. After failing the entrance exam for Tokyo University of Fine Arts and Music four years in a row, he studied art at Sokei Art School in Tokyo (which has no entrance exam). Mr. is not even good at drawing manga-like pictures of lolicom subjects. To be blunt, he is a misfit and a lolicom.

Yet Mr. found a means of turning these negative elements into something positive when he decided to borrow the nickname “Mister” from Shigeo Nagashima, the superstar third-baseman of the post-war Yomiuri Giants. His new name, “Mr.”, intimates the artist’s determination to bear the burden of being Japanese (emulating the beloved sports icon), to position himself as an “artist-entertainer” (like Nagashima, who had a popular and prolific second career on TV), and to exploit his negative qualities (as so many Japanese comedians do).

This uniquely Japanese artist with a knack for entertainment initially created works from the trash he collected, following the examples set by Robert Rauschenberg’s assemblage Pop Art and the Italian avant-garde movement Arte Povera. Mr., however, practiced “poor art” simply because he was too impoverished to buy painting supplies. Arising out of sheer necessity, his junk art was still nothing more than an imitation of other artists’ work.

One day, Mr. decided to explore the imagery of lolicom girls through illustration, imbuing the subject with an ample dose of otaku fantasy. Drawing on the backs of convenience-store and supermarket receipts that he had been hoarding for ten years, he realized that this method somehow echoed Jonathan Borofsky’s “numbered drawings”, for both artists were attempting to enumerate the details of their reality. Mr. quickly went through all of the receipts, and this body of work helped him gain confidence in his art, prompting him to work with various materials. When he was dating a woman whose family owned a sushi restaurant, he borrowed a Japanese sword left by her late father, for use in his performances. Although this girlfriend is long gone, the sword has remained in Mr.’s hands. Highly private episodes like this inform his work, a fact that makes Mr. part of today’s otaku generation.

[Plate 15a; Mr.; “Penyo-henyo” Myomyonmyo Edition (from a set of 4 sculptures); 200422ya; FRP (fiber-reinforced polymer), acrylic, iron; 419

[Plate 15b; Mr.; 15 Minutes from Shiki-Station; 200323ya; Acrylic on canvas; 162